Network Technology Revolution

www.Jobenomics.com

By: Chuck Vollmer

7 November 2014

Download PDF: Network Technology Revolution -7 Nov 2014

The Network Technology Revolution (NTR) could produce tens of millions of net new US jobs. On the other hand, a recent Oxford University study estimates that the NTR could eliminate tens of millions of US jobs due to computerization. Jobenomics believes that both predictions are correct. If so, we should maximize the former and mitigate the latter. To do so, the US needs a strategic framework that is accepted and promulgated by the major NTR corporations, political decision-makers and leading opinion-leaders.

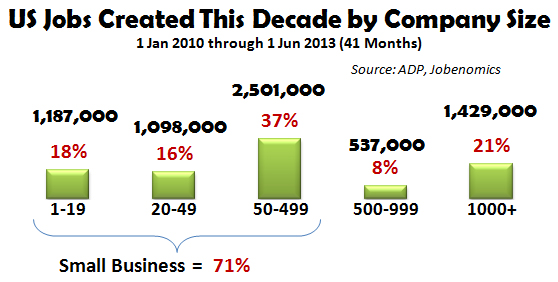

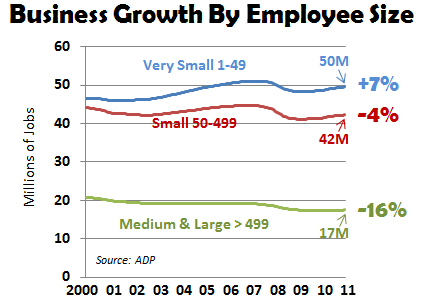

In order for the NTR to produce the maximum number of net new jobs, America needs a strategic framework that maximizes business creation and growth, while simultaneously mitigating business failures. Unfortunately, this framework currently does not exist. American decision-makers and opinion-leaders talk a lot about the importance of small businesses—the engine of the US economy— but their approach to small business creation is laisse faire. Small businesses (<500 employees) employ 77% of all private sector Americans for a total of 91 million employees—almost 5 times the amount of large corporations (1000+ employees each).

If property orchestrated, the NTR could significantly boost business startups, as well as keeping them in business longer. A recent Kauffman Foundation Study[1] finds that net job growth occurs in the US economy only through startup firms. The NTR could create millions of US small businesses if leading American NTR corporations focus on helping our tech-savvy generation monetize social networks and start NTR-related goods-producing and service-providing businesses. Unfortunately, America’s current social media focus is more on entertainment than e-commerce. While the former is nice-to-have, the latter is in the need-to-have category in order increase employment, build business, and grow the economy.

American companies are currently the NTR world leaders. However, this is changing. Chinese companies are rapidly assuming global NTR leadership. Started in 1999 by Jack Ma, a former Chinese English teacher in Hangzhou, Alibaba’s rise has been historic and now is positioned to be the world’s leading NTR Company that specializes in consumer-to-consumer and business-to-consumer e-commerce. Alibaba’s global leadership has been largely underwritten by Americans, starting with a major investment by Yahoo and recently by Wall Street’s largest initial public offering ever. On its first day of trading on 20 September 2014, Alibaba easily surpassed CISCO and Facebook by market capitalization valuation of more than $231 billion, trailing only Google, Microsoft and Apple in value in the highly prized technology sector.

According to Jack Ma, Alibaba was founded[2] “to champion small businesses, in the belief that the Internet would level the playing field by enabling small enterprises to leverage innovation and technology to grow and compete more effectively in the domestic and global economies.” Alibaba’s vision to champion small business creation via the NTR will facilitate prosperity and full employment to a far greater extent than Google, Microsoft, CISCO, Facebook, IBM or Apple’s narrower product and services-oriented mission/value statements. Ma’s strategic vision fits within China’s strategic framework to become the world’s leading economic power, which was accomplished just this year.

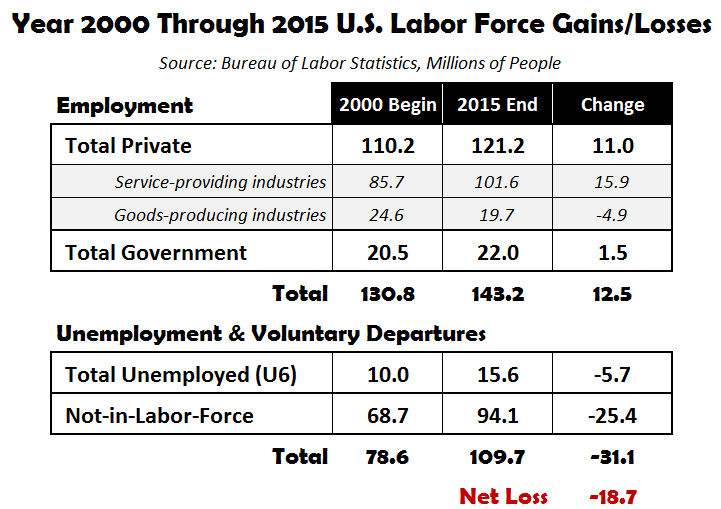

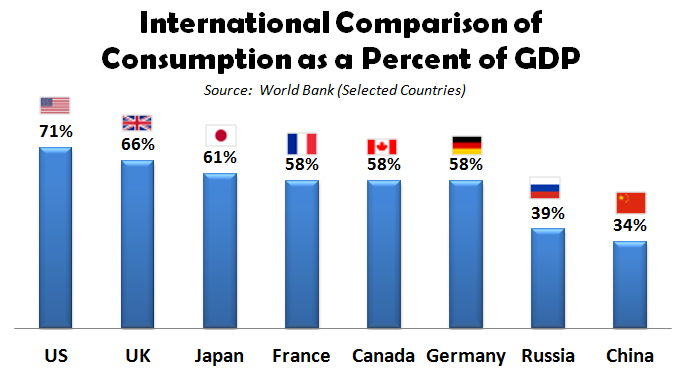

China has now overtaken the USA in GDP based on purchasing power parity (i.e., relative value of the US dollar compared to the Chinese yuan) to become the world’s most powerful economy. Over the last two decades, the Chinese have been able to lift 200 million people from poverty into their work force, whereas in the same time period, 15 million more Americans departed the work force than entered it. As the Chinese have proven, small business creation provides for income opportunity and wealth creation for the maximum amount of people in a society.

From a Jobenomics perspective, more American companies need to champion small businesses that would be enabled by NTR technologies, processes and procedures. The NTR can raise all economies around the world. It does not have to be a zero-sum game.

The Technologies

Technology Revolutions & the Enabling Technologies of the NTR. In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution (IR) transformed America from an agricultural-based society to an industrial-based society. The Military Technology Revolution (MTR) was one of the deciding factors in winning the Cold War and underpinned the creation of the largest and most competitive economic superpower on the planet. In the latter part of the 20th century, the Information Technology Revolution (ITR) ushered in a new era of prosperity and international commerce built largely on the Internet, which evolved from the US military’s ARPA-Net and creative genius of the co-founders of the personal computer, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. Today, the emerging Network Technology Revolution (NTR) has the potential to reshape the global economy. Like the IR, MTR and ITR, the NTR could lead to the creation of tens of millions of new productive jobs, as well as countless economic and social benefits.

The Network Technology Revolution is defined by Jobenomics as the next generation in digital technology that will transform society and economies. The NTR is characterized by a perfect storm of highly advanced technologies, processes and systems, including big data (zettabytes of data stored in “clouds”), semantic webs (thinking websites), machine learning (systems that can learn from data), mobile robotics (automated machines capable of movement), ubiquitous computing (embedding microprocessors in everyday objects to communicate information without requiring human interaction), national broadband system (bringing high-speed networks to everyone ), and the “Internet of Things” (a world where more things are connected to the Internet than people).

Big Data is the term for a collection of data pools so large and so complex that it becomes difficult to process and access the data using traditional methods. For most people who casually use the Internet, their digital world is expressed in terms of kilobytes (103) and megabytes (106). For IT professionals, the digital world is now represented by zettabytes (1021). The World Wide Web has now passed the zettabyte threshold, which is the estimated data storage required to record every written word in the history of mankind. So what does the zetta-flood mean to America’s digital future? Managing gargantuan levels of data is increasingly frustrating due to the complexities and costs of maintaining internal information technology environments. By 2020, the number of data files is projected to grow as much as 75 times, compared to 1.5 times growth of the available pool of IT professionals. As a result, organizations look to the promises of cloud computing to help solve issues related to ever-increasing amounts of big data.

Cloud Computing is as big a paradigm shift away from personal computers (PCs) as PCs were from mainframes in the 1990s. Cloud computing is the practice of using a network of remote servers hosted in data centers to store, manage, and process data, rather than a local server or personal computer. To most people, cloud computing is as amorphous as its name suggests. It is not hard to comprehend that most zetta-data will be stored in the “cloud” due to economies of scale and the decreasing cost of virtualized mega-servers in super data centers. However, the “cloud” is much more than storage alone. It also entails security, connectivity, portability, access, and other issues including privacy, legal and regulatory.

The Semantic Web enables machines to interpret “meaning” much in the way humans do. In the beginning, the World Wide Web (WWW) consisted of non-semantic, read-only websites that focused only on data retrieval. Today’s WWW 2.0 websites are semi-semantic, read-write websites that facilitate data sharing as evidenced by social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) and blogging. WWW 3.0 will introduce fully semantic, read-write-execute websites. WWW 3.0 browsers will perform functions for humans in merged virtual/physical worlds, and will act like personal assistants that learn the interests of users based on their previous activities, avatars that will represent the user’s alter ego in the virtual world, and virtually enhanced 3D worlds that will assist users in their physical world to educate, train, as well as entertain. Technologies in the virtual world are advancing rapidly, especially in the realm of augmented reality (AR) where icons are overlaid (via holographic projections) on your real world view. The US military’s AR awareness and visualization systems, and commercial systems, like Google Glass, will connect the semantic web to humans on the move, providing people with information tailored to their geo-located position and annotated with personalized items of interest via the “thinking” web.

Mobile Robotics involves automated machines capable of movement in multiple environments including factories (movable industrial robots), homes (automated cleaning devices and domestic entertainment robots), infrastructure (pipe and electrical conduit video inspections), surveillance (cameras and other detectors), land (unmanned ground vehicles), sea (autonomous water and underwater vehicles), and aerospace (unmanned aerial and space vehicles). Mobile robotics is a major focus of current research in university, military and security, and medical environments. Nanorobotic technology, which is largely in the research and development stage, will revolutionize medicine, with nanomachines and nanobots one billionth the size of a meter. These devices could be used to attack cancer, dislodge clots and blockages, and perform surgery at the cellular level. Mobile robotics is poised to make a major leap forward with the advent of atomic global positioning that replaces GPS satellites with highly accurate miniature devices that use atomic physics for positioning relative to the earth’s magnetic field. This technology could equip systems with geo-location capability networked with the semantic web and the Internet of Things.

Ubiquitous Computing is also referred to as everywhere computing, pervasive computing and ambient intelligence. Ubiquitous computing is an advanced computing concept that integrates computation into an environment via a myriad of embedded microprocessors in everyday objects (from clothes to animals to inanimate objects) that would be able to communicate information without requiring human interaction. Ubiquitous computing represents the third wave of computing that evolved from the first generation mainframes (each shared by many people), to second generation personal computers (one computer, one person) and third generation ubiquitous computing (many devices communicating to one person). The ultimate goal of ubiquitous computing is to make thinking things to interact with humans anywhere and everywhere.

Machine Learning involves a field of study that gives computers the ability to learn without constant human interaction. Machine learning is a powerful artificial intelligence tool that can make sense of zettabytes of information. For example, machine learning algorithms help email-providers identify spam, and cloud computing-providers eliminate malware. Other applications include automating employee access control, reducing consumer wait times, predicting medical emergencies, self-driving cars and biometric recognition applications. Machine learning and data mining have much in common, where the former is more predictive and the latter more discovery. Data mining finds patterns for humans to understand and machine learning uses those patterns to improve its own program and understanding.

National Broadband. Like electricity was to mankind in the 20th century, broadband will be in the 21st century. National broadband systems will bring high-speed Internet connections to every home and business as part of a national digital infrastructure, which will make individuals and communities more competitive globally. The next generation national digital infrastructure will likely feature a combination of fixed line and wireless broadband connections that will offer affordable, open-access data networks. Currently, only 2/3 of all Americans have access to broadband. The US National Broadband Plan envisions the fastest and most extensive wireless networks of any nation with affordable access for every American. The plan will promote robust competition, reform antiquated standards, policies and laws and reallocate spectrum use, which is vitally important to mobile computing traffic (smart phones, pads and tablets) that is growing at a rate of 300% per year.

The Internet of Things/Everything will make many of the familiar devices and objects in our lives readily Internet-connected, smart phone-accessible and responsive in a world where more things are connected to the Internet than people. The number of devices in the Internet of Things is projected to reach 50 billion by 2020, which equates to more than six devices for every person on earth. To help access big data stored in clouds with billions of personal digital assistants, service providers are developing a myriad of NTR technologies, processes and systems. Closely associated with the Internet of Things is The Internet of Everything. Cisco defines the Internet of Everything as bringing together people, process, data, and things to make networked connections more relevant and valuable than ever before—turning information into actions that create new capabilities, richer experiences, and unprecedented economic opportunity for businesses, individuals and countries.

The Disruption

The NTR Will Be Both Brilliantly Innovative and Creatively Disruptive. Brilliant innovation and creative disruption go hand-in-hand. Brilliant innovation disrupts the status quo by producing something new, more efficient or more worthwhile. The technological combination of big data, cloud computing, semantic webs, mobile robotics, ubiquitous computing, machine learning, national broadband and the Internet of Things will disrupt, displace, or even destroy, existing markets, occupations and the labor force. America is likely to be the first country to deal with NTR disruption since it has the dominant players and the largest free-market economy.

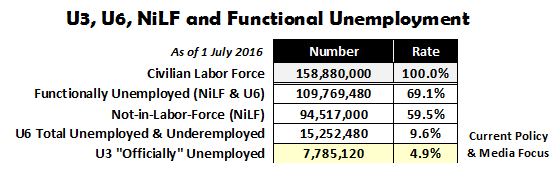

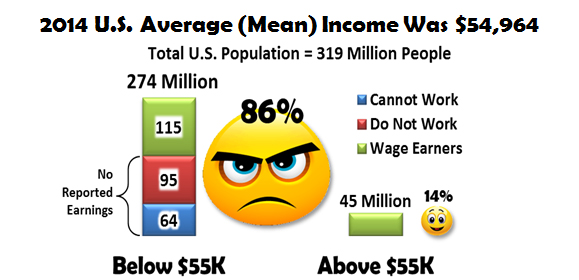

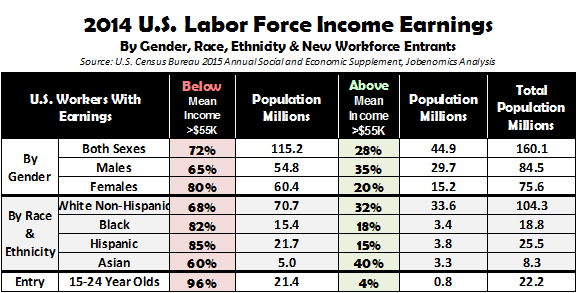

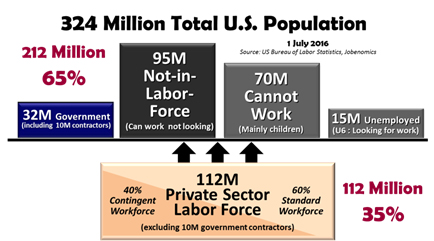

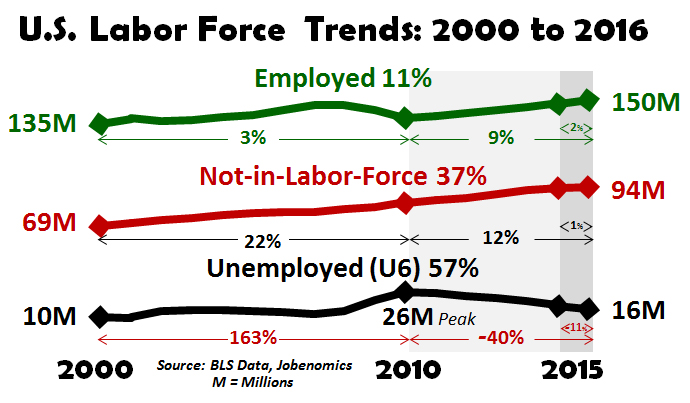

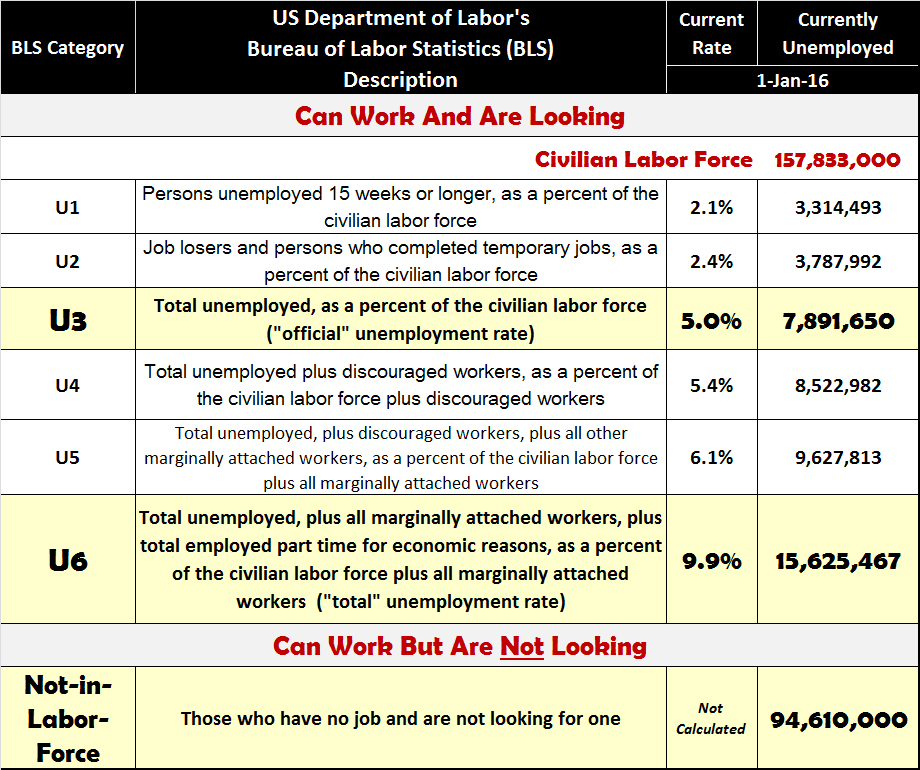

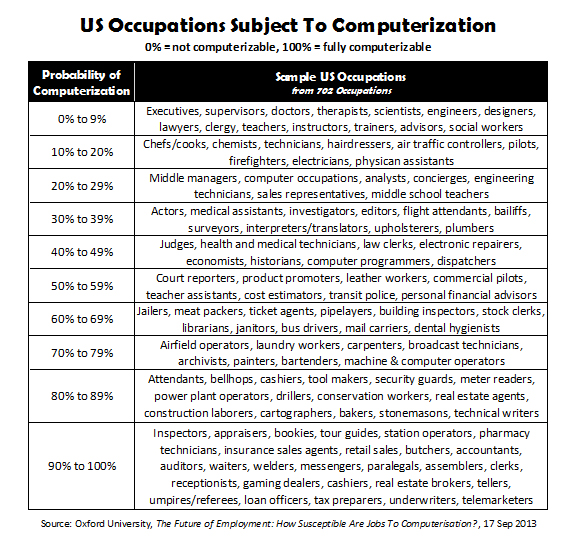

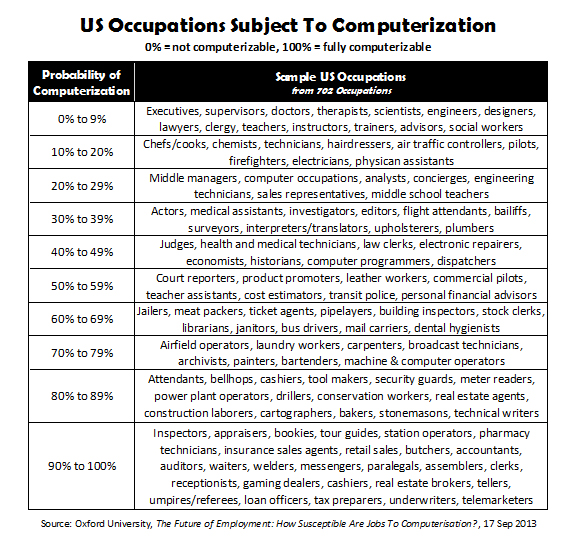

Disruptive Effects of Computerization to the Labor Force. From an employment perspective, the NTR is likely to significantly disrupt the US labor force. According to a recent Oxford University study on computerization[3] “about 47% of total US employment is at risk” over the next two decades. Total US employment is 145 million. If true, up to 69 million jobs could be at risk.

The Oxford University study on the effects of computerization on the American labor force is the first major effort to quantify what recent technological advances may mean for future US employment. Their analysis was mainly from a technological point-of-view to determine what problems engineers need to solve for specific occupations to be automated.

702 occupations from the US Department of Labor were analyzed. The above chart was created by Jobenomics from the Oxford University data to show the probability of computerization of approximately 100 occupations arranged from 0% (not computerizable) to 100% fully computerizable. The study acknowledges that sociological forces will likely restrict many of these jobs from actually being computerized.

Over the last hundred years, technological innovation initially had a destructive effect as technology substituted for labor but, eventually, as new industries and processes became more established, employment expanded along with wages. Many believe that the NRT will be much different in a world of fierce international competition and America’s growing unskilled workforce.

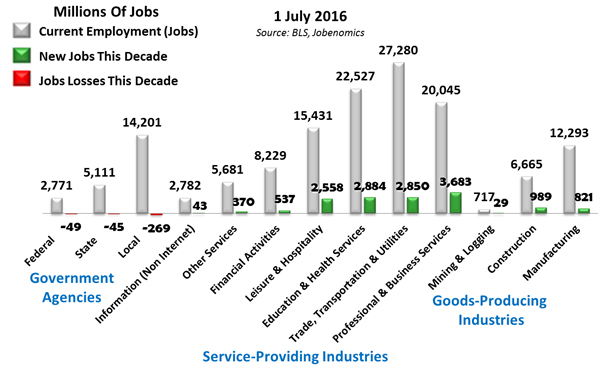

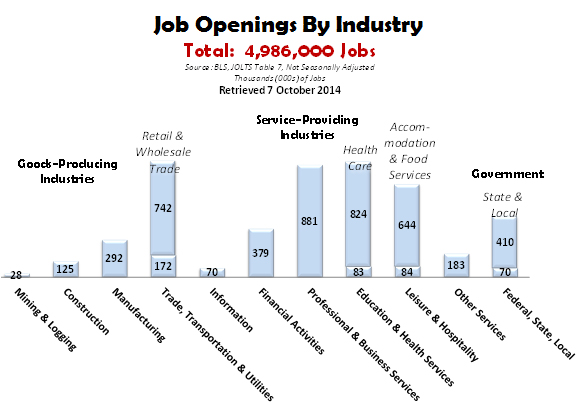

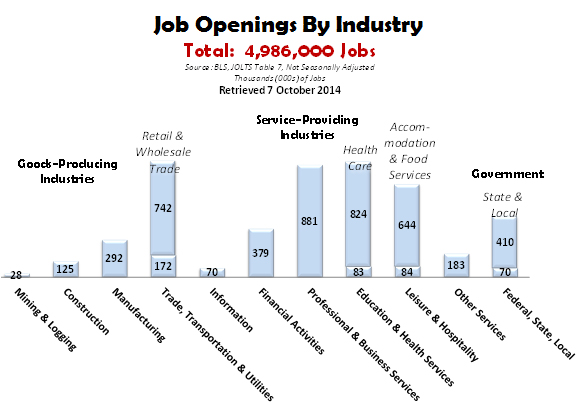

According to the most recent US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Job Openings and Labor Survey[4], there were approximately 5 million unfilled job openings. This survey includes estimates of the number and rate of job openings, hires, and separations for the nonfarm sector by industry and by geographic region. As shown above, every major industry and government had job openings. The primary reason for the large number of job openings is lack of job skills. The lack of qualified workers will encourage increased emphasis on computerization of the workforce, elimination of jobs, and lower employment.

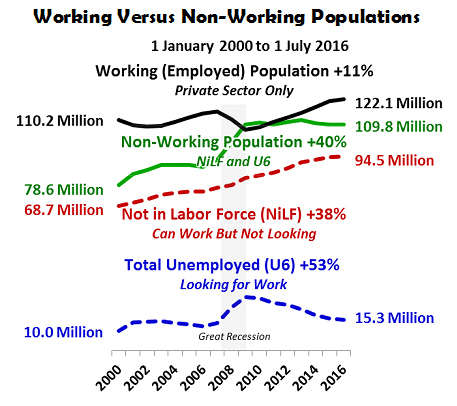

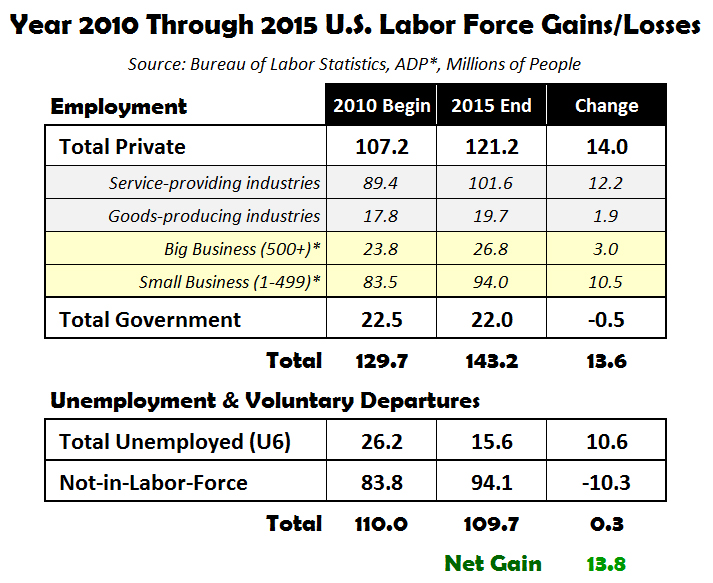

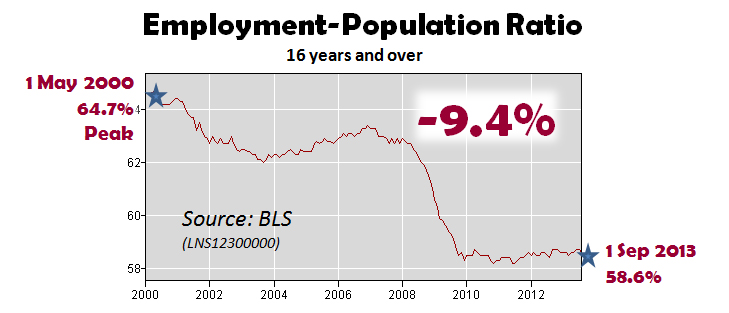

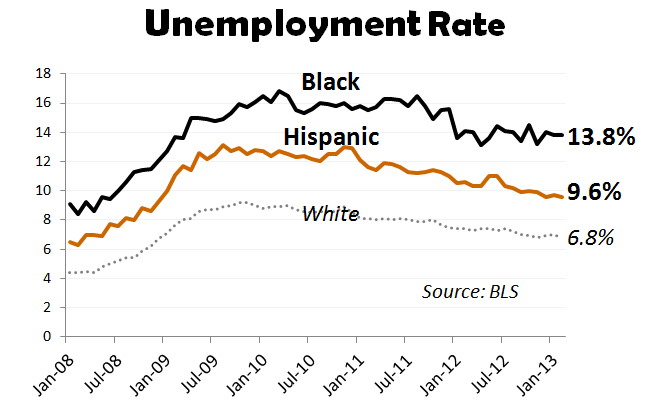

As John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1933, technological innovations pose the threat of economizing the labor force to the degree that it will outrun new uses for dislocated and unemployed laborers. Jobenomics believes that the threat of technological innovation is now accelerating at a higher rate than ever before in US history. Since year 2000, almost 3 times as many Americans departed the US labor force as entered it, with 8,657,000 people entering the US labor force as opposed to 23,929,000 who departed[5]. This is happening on both sides of the U-shaped skills level. Greater and greater numbers of the under-educated and long-term unemployed are losing skills necessary to compete in the new labor force. On the other side of the U-shape, college-educated graduates are finding that their degrees do not meet the needs of the labor market. Unfortunately, American sociological and political forces are not helping. Educational initiatives are not specific enough to adequately qualify new workers for the NTR marketplace. The credo that education is the great equalizer may no longer be true if not focused.

The bottom line is that the NTR will be both brilliantly innovative and creatively destructive. It would be tragic if the US-lead NTR produced millions of new jobs that are fulfilled overseas, thereby forcing many more Americans into unemployment or as wards of the state. American decision-makers and opinion-leaders need to strategically plan to optimize the business and jobs creation capacity of the NTR and the important role that the NTR-providers have to play. As discussed later, Jobenomics believes that this is very doable if the US implements a plan to mitigate losses incurred by NTR disruption by mass-producing small and self-employed businesses that are enabled by NTR technology, processes and systems.

Disruption of the Existing Marketplace Providers. Handheld NTR devices (smart phones/pads/tablets connected to cloud-based data centers) are rapidly replacing personal computers and their related peripherals. According to CISCO[6], in 2013, only 33% of total IP traffic originated with non-PC devices, but by 2018 the non-PC share of total IP traffic will grow to 57%. PC-originated traffic will grow at a combined average growth rate of 10%, while TVs, tablets, smartphones, and machine-to-machine modules will have traffic growth rates of 35%, 74%, 64%, and 84%, respectively. In addition, in 2013, wired devices (mostly PCs) accounted for 56% of IP traffic, but are forecast to decrease to 39% by 2018 as mobile computing devices become prevalent.

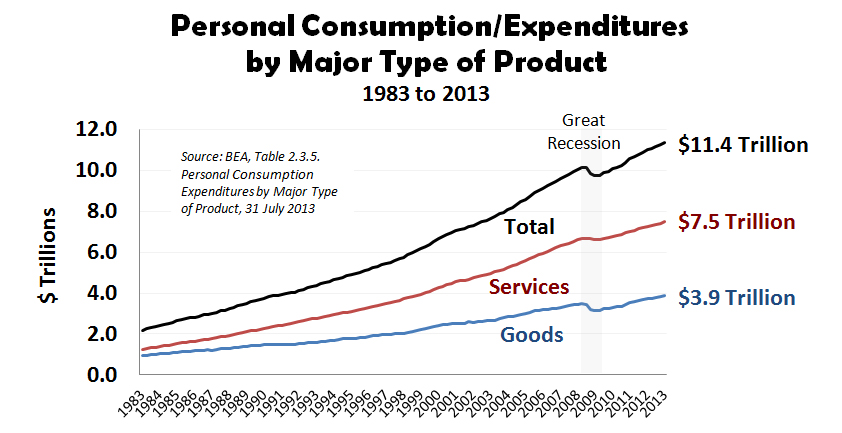

The ITR was dominated by goods-producing industries that sold hardware and software to consumers. The NTR will be dominated by service-providing industries that will own and operate the hardware/software and will provide tailored services to consumers via subscriptions. Personal digital devices cost hundreds of dollars versus thousands of dollars for personal computers and related peripherals. The billions of dollars that are lost in personal computer sales should be offset by billions of dollars made in subscription services by cloud and content providers. It is not inconceivable that competition will drive the cost of handheld devices to near zero as an incentive for long-term contracts for services, much in the same way telephone companies do today with cell phone services.

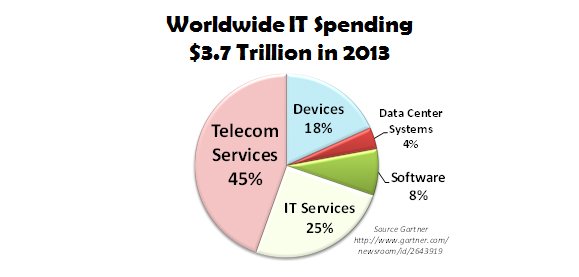

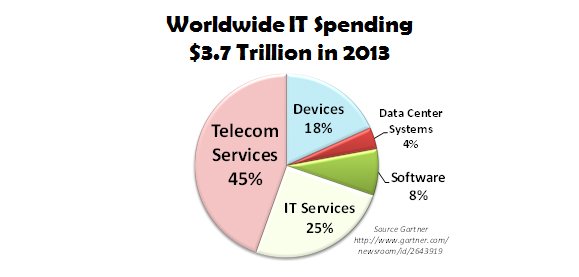

Gartner (a leading IT research and advisory company) forecasts that worldwide IT spending (telecom and IT services, devices, data center systems, software) will grow from $3.7 trillion today to $4.3 trillion in 2017[7]. Gartner breaks down the worldwide market into three segments: emerging (e.g., China), emerged (e.g., New Zealand) and mature (e.g., the US). Emerging and emerged markets spend heavily on devices (mainly mobile phones) and telecom services (mainly mobile voice and data services). Mature markets also spend heavily on devices and telecom services, but, compared to the emerging and emerged markets, are overwhelmingly investing on data center systems (servers, storage, and network equipment), software (enterprise and infrastructure), and IT services (business and IT product support). Consequently, the US is likely to dominate the NTR in the near-future vis-à-vis their investment in core technology and systems (networks, data centers, cloud computing, machine learning, software, services, etc.) whereas most of the rest of the world is spending on NTR devices and subscription services.

In 2013, information technology market spending was 70% services-related and 30% goods-related (devices, data centers and software). Jobenomics believes that services-providing industries will become even more dominant as the NTR matures. Jobenomics also forecasts that subscription-based revenues will be preferable to consumers than sales of individual products and traditional service fees because the transition from the ITR to the NTR will be dynamic and complicated. Consumers will likely be attracted to the NTR provider with the best brand who will manage the consumer’s network-centric architecture at the lowest cost. For individual consumers, their network will largely consist of integrated personal devices (from smart phones, to PDAs, to entertainment devices) and their connectivity to highly reliable networks and content providers. For government and corporate consumers, their net architecture will likely consist of a complex combination of public, private and hybrid enterprise-wide networks. Today’s service providers are categorized as software, platform or infrastructure as a service (SaaS, PaaS, IaaS, respectively) providers. The future NTR-service provider of choice will be the one that unifies all three categories, is able to strategically position and rapidly reposition their clients in a dynamic digital ecosystem, and offers the most integrated, secure, low-cost, and digitally portable subscription service.

The NTR will present huge revenue opportunities for collaborating NTR institutions. Joint ventures, mergers and acquisition will be the norm as the NTR marketplace rationalizes itself into winners and losers. Dominant NTR companies will have an initial advantage, but the field of exciting new NTR providers and vendors is growing exponentially. NTR competition will be fierce between content providers, equipment manufacturers, software providers, social-networking giants, service providers, niche and emerging players.

Competition for new markets has just begun. Relatively unknown new network-centric companies are likely to displace today’s information service providers in the same way the information service providers replaced telecommunications companies that dominated the information marketplace twenty years ago. In the last 18 months, over a dozen niche players have gone public, fetching tens of billions of dollars’ worth of investment capital. If subscription services become the norm as forecast, content providers may emerge as dominant players in the NTR, especially considering the fact that video traffic (TV, video on demand, etc.) constitutes the majority of all consumer Internet traffic. International competition cannot be understated. US hegemony in the NTR marketplace could be upended as well-financed, foreign innovative solutions enter the competition for IP traffic (Internet Protocol where data is sent from one IP address to another).

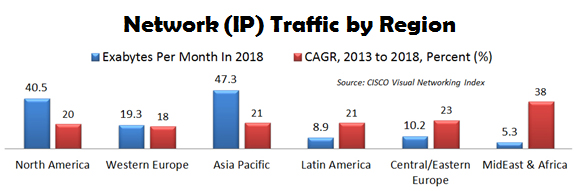

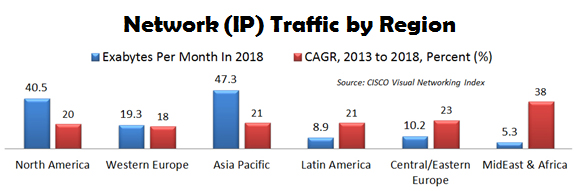

In terms of network IP traffic, North America will only consume 31% of the total traffic in 2018[8]. Asia Pacific will be the largest consumer and MidEast/Africa will be the fastest growing. In Asia, China is the dominant player. China is currently dominated by Alibaba that controls 90% of the consumer-to-consumer and 51% of the business-to-consumer e-commerce. More importantly to international e-commerce, with the Chinese government’s permission, Alibaba locks out competitors (like Amazon) by allowing global consumers to only search Alibaba’s content from within Alibaba’s websites. As Jack Ma says, “Today is cruel. Tomorrow is crueler. And the day after tomorrow is beautiful.” International competition is likely to be as cruel as it is innovative.

Disruptiveness of Connectivity. The NTR will be significantly more disruptive—technologically, economically and sociologically—than its ITR predecessor. The ITR started in the 1960s with the first commercial uses of mainframe computers, followed by the Internet, personal computers, word processing, e-commerce, industrial robots, self-service technology, bar-code scanners, RFID sensors, personal digital assistants, and the like. The 20th century ITR was more oriented to “sustaining innovation” that created tens of millions of net new jobs by evolving existing industries and introducing new industries with products that consumers wanted. In contrast, the NTR is likely to be more oriented to “creative destruction” that will upend existing markets and value networks.

Soon everyone will be connected to every significant thing and person anywhere. In contrast to the physical world, the virtual world frees us from physical limitations of birth, class and geography. This sense of freedom empowers the individual over the organization, which makes state and institutional governance more problematic. Consumers, activists and entrepreneurs will be able to create products and ideas that could challenge the status quo and usher in a new era of globalization based on new communities-of-interest and non-traditional ideas.

It is unclear if the freedom of movement through the virtual world and freedom of information in a relatively unstructured, unbounded ecosystem will be ordered or chaotic. Innovation and new ideas generally originate from outside traditional institutional bulwarks. Within a matter of a decade, five billion new minds, mostly from the developing world, will join the NTR. Without doubt, their notion of fairness and equity will be far different from that of the developed world. Depending on the scalability of new global initiatives or experiments, the consequences could be revolutionary as tens of millions join cause célèbres that challenge tradition. Consequently, the NTR is likely to be more chaotic than ordered, and driven more by international rather than domestic consumers.

Disruptive Effects of Cybercrime & Cyberterrorism. The NTR will usher in an era of cybercrime that could literally facilitate the largest negative transfer of wealth in history. A landmark study conducted by CSIS and McAfee[9] estimates that the annual cost of global cybercrime is between $300 billion and $1 trillion with more than half this amount focused on four major countries: United States, China, Japan and Germany. The study also calculates that cybercrime cost the USA over 200,000 jobs last year and predicts that the number of job losses will grow steadily as more businesses and individuals move online globally. The most important cost of cybercrime is the damage it does to national economies due to the theft of intellectual property, the negative effect it has on innovators and investors, and the additional costs of securing networks, recovering from cyber-attacks and fixing damaged reputations.

The difference between cyberterrorism and cybercrime is subtle, but powerful. The former is largely motivated by ideology and the latter by greed. As bad as cybercrime may be, cyberterrorism could be much worse, especially if conducted by well-financed state-sponsored organizations with the intent to disrupt the stability of countries or destabilize the global balance of power. In a world defined by different ideologies, cyberterrorism could become the weapon of choice that can be deployed directly or as a clandestine element of indirect warfare via surrogates who can provide plausible deniability for the originator. As a superpower, the US tends to prefer direct warfare. America’s less-resourced enemies tend to prefer the asymmetric advantages of indirect warfare to exploit America’s largest vulnerability—its openness. Since the NTR is a global revolution, NTR technology, processes and systems will be available to a wide array of American adversaries. Properly orchestrated, NTR could be used as a weapon of mass disruption by cyberterrorists.

Cybercrime and cyberterrorism will be growth industries for the foreseeable future. Consequently, it is imperative that government and major civilian institutions collect and publish data on adversaries and establish policies that will mitigate risk to the constituents they serve. Today, the advantage is on the side of hackers and attackers as opposed to defenders. Consequently, the US will need much more than an effective cyber-defense. State-of-the-art cyber-offence weapons and cyber-ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) assets will be needed as well. Without cyber-offence and cyber-ISR, major state-sponsored cyber-terror organizations cannot be held at bay. For countries like Iran, Russia and China, a form of cyber-MAD (mutually assured destruction) could hold enemies at bay as was done during the Cold War. For non-state actors like ISIS and Al Qaeda, MAD probably will not be effective. However, cyber-ISR would be effective in identifying terrorists and their supporters, and the cyber-offense could take down their web-based command, control, recruiting and financial systems.

Until major policy changes are made and actions implemented, cybercrime and cyberterrorism are likely to be deleterious to the US economy and employment to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars and millions of jobs. NTR corporations should play a major role in counter-cybercrime and counter-cyberterrorism, since they are the ones who are building the very systems that could lead to their demise.

Disruption to Privacy. Not all disruptions to privacy are unwanted. Many have practical uses. Geofencing is one such example. Geofencing is a location-based application that lets administrators send messages to recipients entering a defined geographic area. Ankle bracelets use geofencing. Fleet managers use geofencing to keep drivers on route and on schedule. Via geofencing, security managers are alerted if employees enter unauthorized areas or if RFID-tagged equipment is not where it should be. Shopping malls use geofencing to send coupons to customer cellphones when near a participating store.

On the other hand, many disruptions to privacy are unwanted. Resolving right-to-privacy against the right-of-the-public to obtain relevant information will prove to be a difficult and complex process. In the physical world, the right-to-privacy is part of most legal traditions that restrains government and institutional actions that threaten a person’s right to seclusion, confidentiality and personal autonomy. The virtual world is not yet limited to such traditions and may be largely immune to such limitations.

The Internet is the world’s largest ungoverned space not bound by territory and largely immune to political, legal and institutional forces. The era of the cyber-paparazzi is just beginning. Damaging information will be very hard to delete once it goes viral. The “Celebgate” scandal—the hacking of approximately 200 nude celebrity photos in August 2014—shows that even stored cloud data may not be secure from invasions of privacy. As evidenced by the hacker attacks to millions of big-box store customer accounts and the Assange/Snowden leaks of classified government data, intrusion of highly secured data is, and will continue, to be an issue. Consequently, traditional privacy rights will be extremely difficult to preserve in tomorrow’s ultra-networked Internet-of-Everything world where everything of significance is recorded, cataloged and stored. The NTR will make the delete button largely obsolete, especially for those with the intent and resources to retrieve even the most secure or supposedly destroyed digital data.

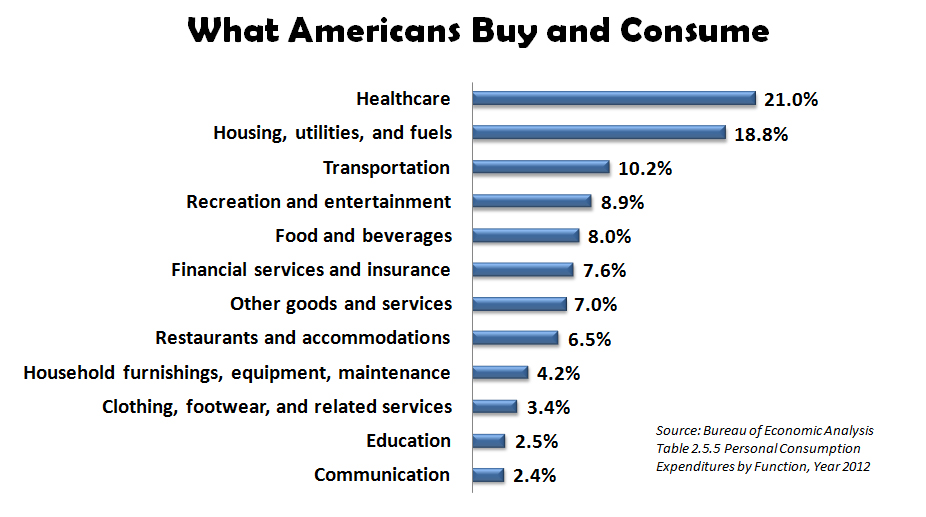

Big Data has already spawned a billion dollar a year data-brokering industry that lacks transparency and accountability. Data-brokering involves the collection of information from the zettabytes of data within the realm of Big Data to produce detailed portraits of individual Americans and their buying habits. According to a Federal Trade Commission report[10], data brokers collect personal information about consumers from a wide range of legal sources (public and private records, online activities, social media, credit card purchases, loyalty programs, magazine subscriptions, etc.) and provide it for a variety of purposes, including consumer profiling, identity management, marketing, political campaigns and fraud detection. Profiles are often used to measure creditworthiness, insurance, employability, as well as inclusion or exclusion from social groups. Profiles are often sold without the individual’s knowledge or ability to correct false or misleading information. It is a sad aspect of today’s society that data brokers often know more about individuals than do their family and friends.

With the exception of politicians and celebrities, most people’s personal identity outweighs their online identity. With the advent of the NTR, this is likely to change, especially for the millennial generation that was born into the digital age and have invested significant time and energy posting intimate details of their lives in social media. Most of this online information is captured in some data center and ripe for harvesting. A person’s online identity is becoming more and more important as people’s lives are correlated, cataloged and assigned to various economic, social, demographic, religious, political, cultural, geographic, educational and splinter groups. It is conceivable that an online identity rating could be as important as today’s credit rating. Identity managers will be needed to help individuals manage their online identity as well as correct or redact incorrect, misleading or malevolent content.

The European Court of Justice’s decision to introduce a mechanism for individuals to delete private information from Google will be a bellwether case that will be closely watched. Even if the European Court is successful, it only addresses the tip of a very big data-storage iceberg. Redaction of data that may reside in multiple locations with zettabytes of other data will be challenging to entirely identify, retrieve, redact and verify.

The Solution

Network Technology Revolution and Micro-Business Creation. Jobenomics defines micro-businesses as very small (1-19 employees) and self-employed (0 employees other than the owner) businesses. While the vast majority of micro-businesses stay small, some do not. Bill Gates and Steve Jobs started a micro-business in 1975/76 and became the pioneers of the Internet Technology Revolution. Today, Gates’ Microsoft and Jobs’ Apple are worth over $1 trillion, employ 225,000 people, and have facilitated the creation of millions of micro-businesses and tens of millions of other jobs. The NTR has the same potential as its ITR predecessor if today’s pioneers enable the creation of millions of micro-businesses.

In the same way that the industrial age upended the agricultural age, the NTR will enable the information age to upend the industrial age and transform the American labor force as well as the very nature of work. Micro-business will likely play a much larger role than ever before. Jobs will increasingly be dissected into discrete tasks, which, in turn, will be addressed by temporary collectives and virtual organizations. Team collaborative and management tools (such as SharePoint) will further create “contextual” work environments that rapidly form, perform, and then reform to address subsequent tasks. More and more brick and mortar edifices will give way to hoteling and mobile computing. Contingency workers (consultants, independent contractors, independent professionals, temporary contract workers, part-time workers, seasonal workers, freelancers, etc.) will continue to replace full-time employees. Contingent work will significantly boost micro-business growth as contingency workers become the norm, up from 31% of the US labor force in 2008 to an estimated 40% in 2020[11].

NTR-enabled temporary alliances that can rapidly respond to short-term tasks are ideally suited for micro-businesses that tend to be more eager and entrepreneurial than big business. Either by nature or by necessity, contingency workers are entrepreneurial, are a reasonable response to today’s changing marketplace, and offer firms workforce flexibility during seasonal or uncertain times. On the negative side, firms can take advantage of contingency workers who often receive lower wages than permanent workers. Since many contingency workers are not employees, they are not subject to labor and employment laws, nor does the firm has to pay employee-related benefits and taxes. The way to mitigate many of these negatives is to encourage contingency workers to incorporate their own micro-businesses that will provide tax revenues, labor and employment.

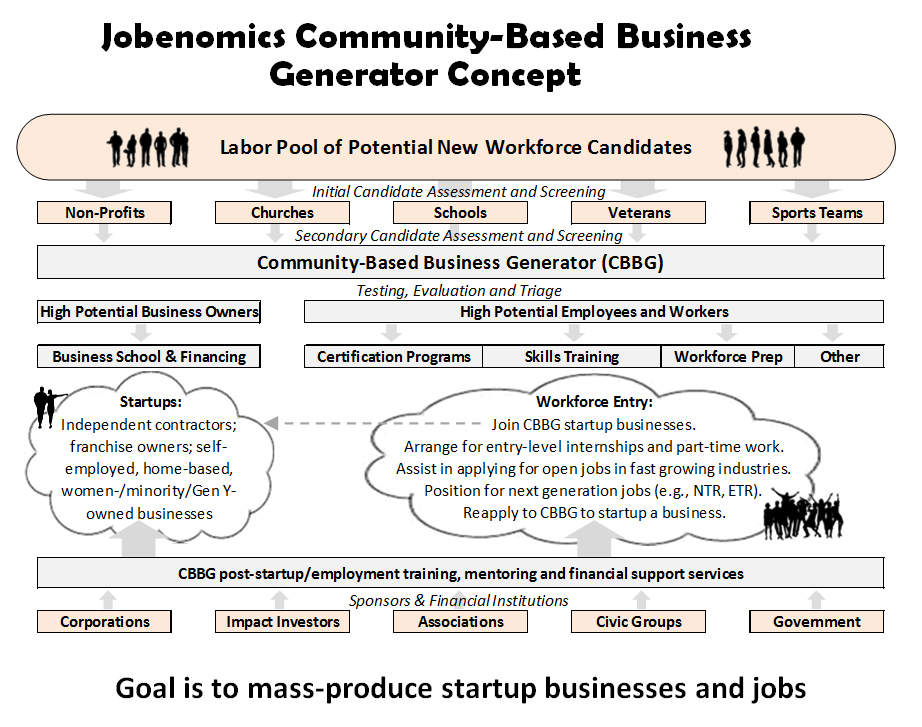

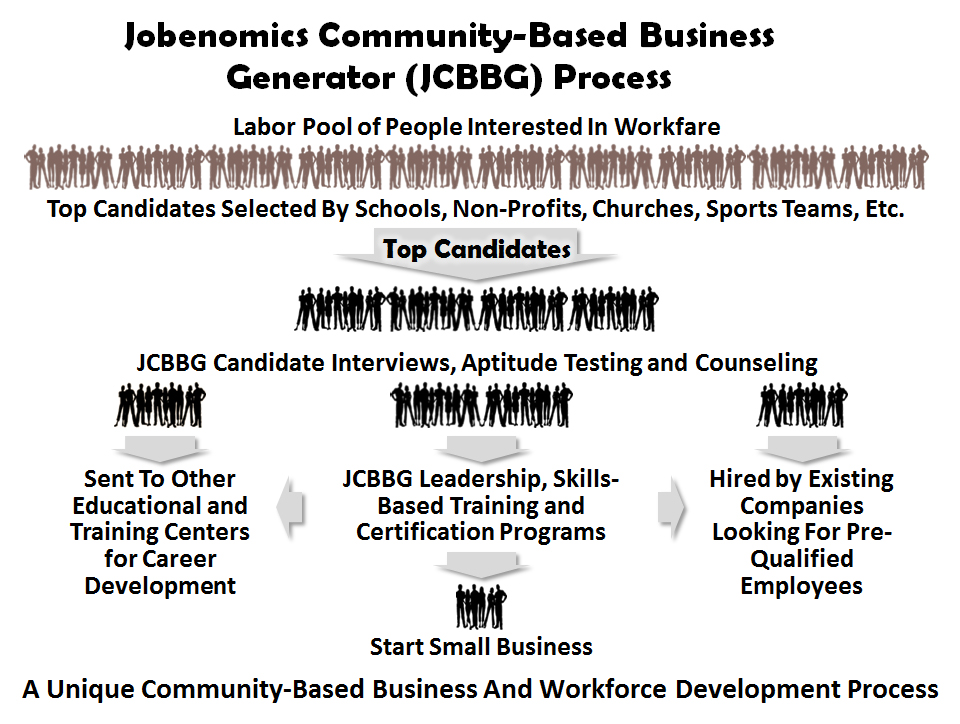

Jobenomics believes that an American NTR Micro-Business Initiative could boost American employment by over 20 million people within a decade. Most government and big business pundits consider this wishful thinking. But ask any small business owner or serial entrepreneur if this is doable and they would say “Absolutely!” If the CEOs of America’s leading NTR corporations collaborated to monetize the social networks that they control, millions of new US micro-businesses could emerge. Jobenomics invites CEO participation to build local business generators that mass-produce micro-businesses at the base of America’s economic pyramid. The objective of the Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator initiative is to increase birth rates of startup businesses, extend the life span of existing businesses, and increase the number of employees per business.

Jobenomics predicts that the NTR could enable the mass production of millions of micro-businesses. The NTR could be the great business equalizer that allows home-based, self-employed businesses to compete globally with much larger firms. Today, WWW 2.0 social networks focus mainly on media, entertainment and shopping. Tomorrow’s WWW 3.0 social networks may be able to monetize the World Wide Web, creating tens of millions of new jobs. eBay, a WWW 2.0 startup in 1995, is now a multi-billion dollar enterprise located in over 30 countries, with 31,500 employees that enable millions of global micro-businesses. If properly supported, WWW 3.0 could create dozens of eBay 3.0-like enterprises.

As mentioned earlier, Alibaba defines its role as a small business champion and is aggressively supporting millions of business startups and existing business expansion in China. In 2013, two of Alibaba’s web stores (Taobao’s consumer-to-consumer store and Tmall’s business-to-consumer store) handled $240 billion in sales, more than eBay and Amazon combined, and are on track to handle $1 trillion per year[12] in transactions with emphasis on small business. Alibaba provides free startup services and micro-business loans as part of their network services. According to Alibaba, their micro-business loan book is over $2 billion/year with a non-performing-loan ratio below 2%. With an average loan of $8,000, Alibaba underwrites approximately 250,000 micro-businesses per year.

If Mark Zuckerberg used Facebook to monetize social networks, millions of new jobs could be created. If John Chambers spent as much time developing the Internet of Business as opposed to CISCO’s Internet of Things, millions of new businesses could be created. If Tim Cook turned Apple’s creative energy to creating NTR-optimized iBusiness devices, billions of people around the world could be given the opportunity to conduct or build a business. The same is true of Jeff Bezos and Amazon, Satya Nadella and Microsoft, Larry Page and Google, Ginni Rometty and IBM, as well as the rest of the American CEOs involved in the NTR.

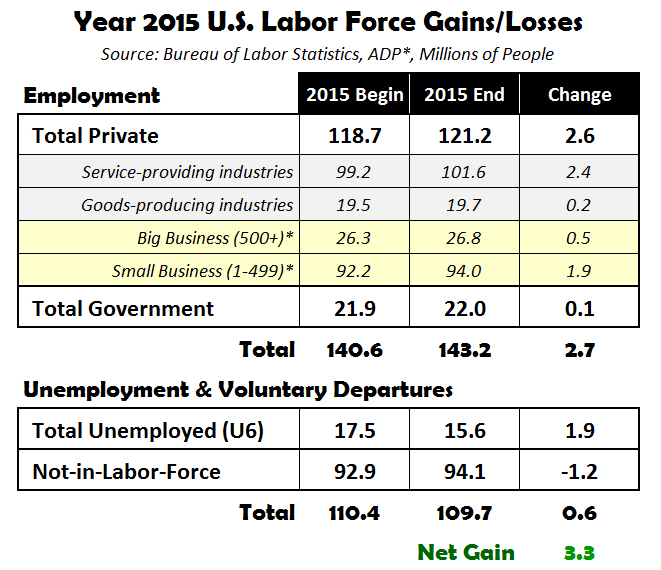

Small business is the engine of the US economy. According to the US Small Business Administration[13] there are 17,700 big businesses and 28.2 million small businesses with fewer than 500 employees. Of the 28.2 million small businesses, approximately 5 million are employers and 23 million are self-employed. As reported by the ADP National Employment Report[14], small businesses employ 77% of all private sector Americans with a total of 88.7 million employees—5 times the amount of large corporations (1000+ employees). Very small businesses with fewer than 19 employees employ 65% more than all large corporations combined (29.7M versus 18.0M). Since the beginning of this decade, small business has produced 73% of all new American jobs. This is an amazing statistic, considering the adverse lending environment, mounting regulation, and the pittance of government funds allocated to small businesses.

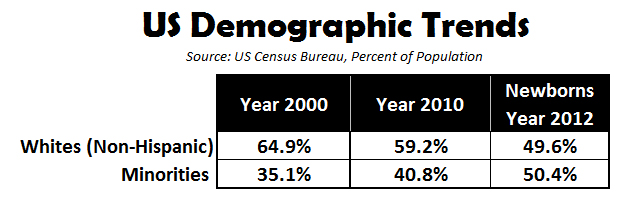

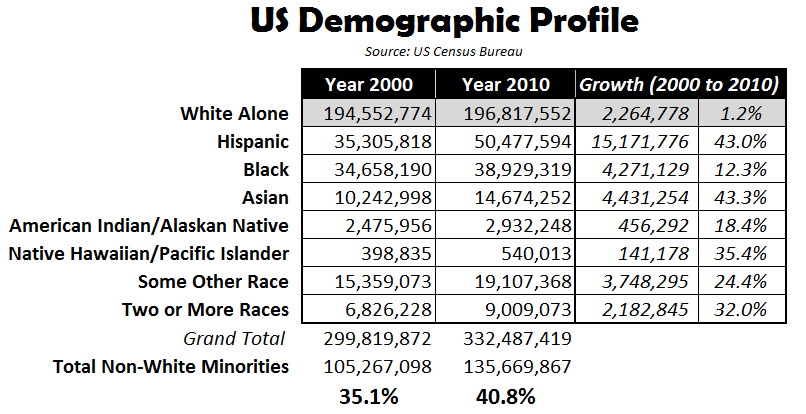

Jobenomics believes the four US micro-business sectors with the highest growth potential are Generation Y-owned, Women-owned, Minority-owned, and Veteran-owned businesses. In this regard, Jobenomics has been collaborating with experts on how to enable micro-business creation in these four sectors. Their recommendation was to create a holistic web-based platform with back office and subscription services for startups. This platform would provide a turnkey solution including e-commerce, secure cloud computing, semantic webs, financing, loans and mentoring. These services would initially be free to encourage the participation of aspiring entrepreneurs and contingency workers who would like to be business owners.

If Jobenomics can help create thousands of highly-scalable micro-businesses, via the Network Technology Revolution, America writ-large can facilitate creation of millions of micro-businesses that would transform the US economy. With the leadership and commitment of the leading NTR corporations, 2015 could be a break-out year for small businesses that traditionally have been the primary source of employment for entry-level workers and the long-term unemployed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Network Technology Revolution can be either a blessing or a curse depending on how it is managed. If managed properly, it can generate millions of new businesses and tens of millions of new jobs. If poorly managed, the effects of computerization could potentially eliminate tens of millions of current US jobs, as well as disrupt the US economy. From a Jobenomics perspective, the onus is on the leading NTR corporations—the pioneers of the 21st century digital age. It is within their capability, and self-interest, to maximize the benefit of the emerging NTR technologies, processes and systems that they are developing. If they don’t, others around the world will, as history attests.

The phrase “Nation of Shopkeepers” first appeared in The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith in 1776. Smith believed that when individuals pursue their self-interest, they indirectly promote the greater good of society. Smith argued that merchants, seeking their own self-interests, contribute significantly to the commonwealth by producing vital goods, services and tax revenues. Without this “invisible hand,” societies would be incapable of effectively pursuing self-sufficiency, prosperity and wealth creation. Jobenomics agrees and believes that the United States is likely to further evolve into a “Nation of Small Businesses” as we exploit economic opportunities enabled by the Network Technology Revolution.

[1] Kauffman Foundation, The Importance of Startups in Job Creation and Job Destruction, 9 Sep 2010, http://www.kauffman.org/what-we-do/research/firm-formation-and-growth-series/the-importance-of-startups-in-job-creation-and-job-destruction

[2] Ibid 1, last paragraph

3 Oxford University, The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs To Computerization?, 17 Sep 2013, http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdfhttp://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf

[4] S Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Survey, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.htm

[5] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation Summary, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm

[6] CISCO, Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2013–2018 by Device Type, http://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/collateral/service-provider/ip-ngn-ip-next-generation-network/white_paper_c11-481360.pdf

[7] Gartner Worldwide IT Spending Forecast, http://www.gartner.com/technology/research/it-spending-forecast/

[9] Center for Strategic and International Studies and McAfee study: Net Losses: Estimating the Global Cost of Cybercrime, June 2014, http://csis.org/files/attachments/140609_rp_economic_impact_cybercrime_report.pdf

[10] Federal Trade Commission, Data Brokers, May 2014, http://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/data-brokers-call-transparency-accountability-report-federal-trade-commission-may-2014/140527databrokerreport.pdf

[11] Bloomberg Business Week, 20-25 October 2014 Edition, Companies/Industries, Page20

[12] International Business Times, Alibaba IPO: 5 Reasons Why The Stock Is Not Overvalued, 19 Sep 2014, Gordon Orr, Chairman of McKinsey Asia, http://www.ibtimes.com/alibaba-ipo-5-reasons-why-stock-not-overvalued-1692191

[13] US Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/FAQ_March_2014_0.pdf

[14] ADP National Employment Report, http://www.adpemploymentreport.com/