Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generators

www.Jobenomics.com

By: Chuck Vollmer

15 August 2016

Download PDF:

Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generators - 15 August 2016

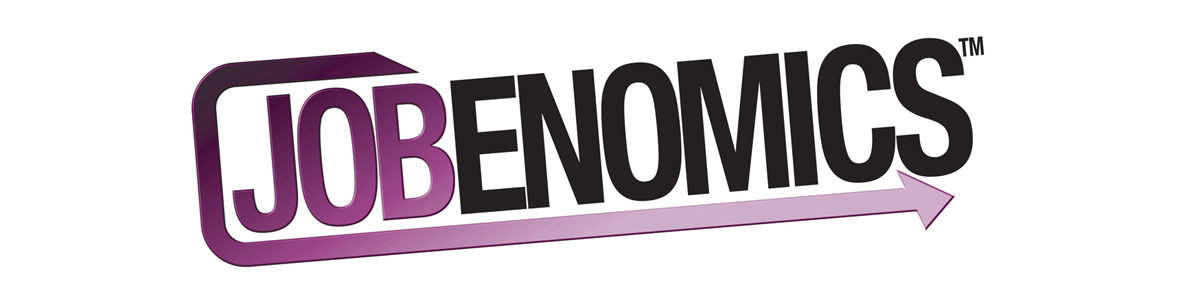

The way that government and big business can plan, manage and support small business and job creation is via community-based business incubators, business accelerators and business generators.

Business incubators tend to focus high-tech, silver bullet innovations that have extraordinary growth and employment potential. Business accelerators focus on expanding existing businesses in order to make them larger and more profitable. The Jobenomics business generator concept involves mass-producing small and self-employed business with emphasis on lower-tech but plentiful service-providing businesses at the base of America’s economic pyramid. Many cities have business incubators, usually located at or around universities or technology parks, and business accelerators that are associated with mezzanine financing institutions. Jobenomics is working with cities and states to create business generators to mass-produce startup small and self-employed businesses.

Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generators mass-produce startup businesses by: (1) working with community leaders to identify high-potential business owners and employees, (2) executing a due diligence process to identify potential high quality business leaders and employees, (3) training and certifying these leaders and employees in targeted occupations, (4) creating highly repeatable and highly scalable “turn-key” small and self-employed businesses, (5) establishing sources of startup funding, recurring funding and contracts to provide a consistent source of revenue for new businesses after incorporation, and (6) providing mentoring and back-office support services to extend the life span and profitability of businesses created by the Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generators.

The process starts by using community leaders to identify high potential job seekers. Churches, non-profit institutions, schools, sports teams and veterans groups are a great source for identifying talent, desire and fortitude. These organizations provide the first phase of the triage process by screening and assessing high performance people who are known to them. The second stage is accomplished during onboarding that involves Jobenomics screening and assessing. The third stage uses aptitude and personality tests to determine potential career paths.

Once completed, candidates will be separated into a business leader group or a high potential employee group for training. The leader group will undergo management and startup business training. The employee group will undergo skills training based on the role that they will assume in the startup business (operational, technical, mechanical, financial, marketing, administrative, etc.). After the training is completed and certifications awarded, the team will commence startup operations under the guidance and assistance of the Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator team. Jobenomics contends that Community-Based Business Generators could vastly improve the rate of startups and expanding businesses, and reduce the rate of contracting and closing businesses.

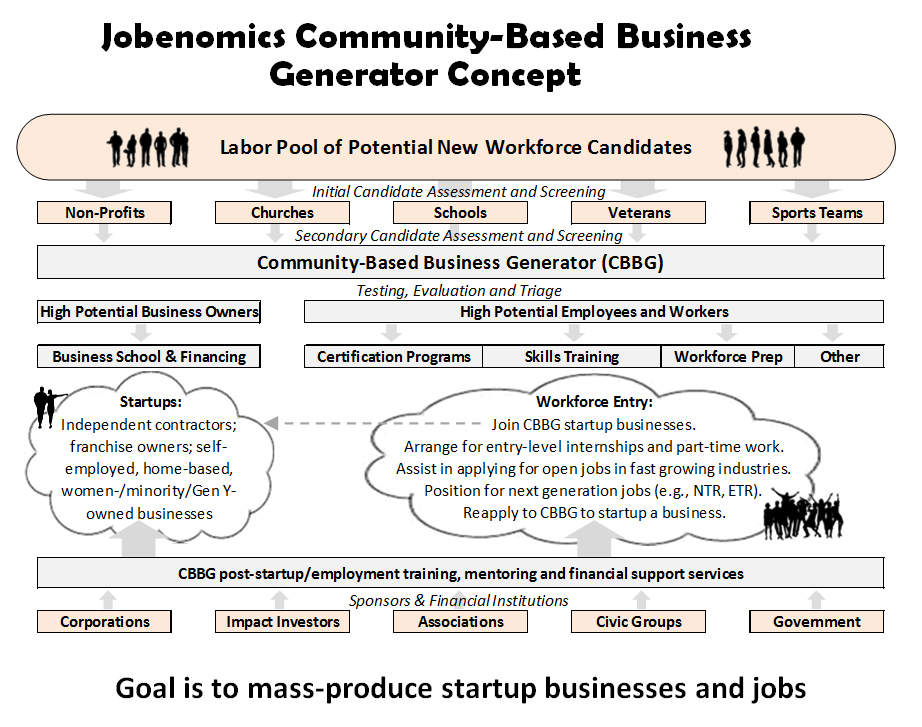

Starting with a notional pool of thousands of candidates, Jobenomics will work with local civic organizations (churches, non-profits, sports teams, etc.) to identify and nominate the top 30% to 50%, who they know, for the Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator program. This is the first stage of the due diligence process to separate the proverbial wheat from the chaff.

These nominees will then be subjected to standard aptitude and attitude tests in order to identify and assist those (1) those that should be sent other educational (GED and postsecondary) or training (vocational) centers for career development, (2) those that are qualified and suitable for immediate employment with existing companies, and (3) those that desire and have an aptitude for starting a small or self-employed business. Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator will help all people who enter the program to find meaningful employment and career paths.

Jobenomics envisions that 25% of the nominees would seek a traditional education and training path, 25% would be hired directly by existing business who are looking for quality workers, and 50% would seek a more independent and self-sufficient route offered by a small business startup or self-employment.

Of the 50% that choose the Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator training and certification process, Jobenomics anticipates that approximately 25% will eventually implement a small business startup or incorporate as a self-employed business. The 75% that undergoes but does complete Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator process will be certified (with empirical data by professional testing and evaluation) as high-quality candidates for immediate employment or traditional education/vocational training.

Many of the initial candidates are likely to prefer working for existing companies rather than going through the Jobenomics process. Anticipating this, Jobenomics will implement a “pipeline” to connect these individuals who have undergone some level of due diligence to companies that are hiring. Consequently, the Jobenomics management team includes a nationally recognized leader who developed such a pipeline system that has matched 250,000 veterans with companies. This system is ideally suited for matching Jobenomics candidates to local employment vacancies.

The overall objective is to mass-produce small and self-employed businesses, which makes the Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator process unique as a traditional business and workforce development center. Traditional workforce development processes focus on preparing potential workers for employment by existing businesses—usually large corporations. For marginalized individuals at the base of the American economic pyramid (especially those in depressed urban and rural areas) the odds of employment at existing businesses are slim as evidenced by the long lines at traditional job fairs versus the low percentage of people hired.

The Jobenomics process focuses on preparing workers for starting a business, whether they actually start one or use the experience to be more competitive to get a job. In today’s world, gainful employment is difficult and oriented to those that are currently employed, credentialed or high-skilled. Conversely, a common complaint that Jobenomics often hears from companies is that they have a very hard time (1) finding good people who want to work, (2) who have the right attitudes and aptitude for work, and (3) who have workforce credentials, experience or related skills.

Every nominee that enters the Jobenomics process will setup a self-employed business, which can be incorporated in a matter of days, and undergo elementary business training. The reason for setting up a small business is to make them more competitive in today’s job market. Many employers prefer to “try before they buy”. An incorporated self-employed individual can position themselves for subcontract or contingent work (1099) as a prelude to standard full-time work (W2). Even if a self-employed individual never receives an income as a self-employed business, that individual can present themselves with credentials (Employer ID Number, website, business card and skills resume) that align with the business community. In addition, Jobenomics will provide additional credentials regarding the individual’s workforce aptitude, skills and suitability tailored to the specific hiring opportunity. Jobenomics credentialing, along with letters of recommendation from the nominees’ sponsoring organization, will greatly distinguish the individual from the masses of unemployed or new or returning workforce entrants.

Today, the United States does not have standardized national, state or local processes to create or mass-produce startup businesses. The U.S. startup process is largely ad hoc. By instituting a community-based (all jobs are local) standardized, repeatable and scalable process to mass-produce startup businesses, millions of new establishments could be created across America. By being part of a small business team, team members will be motivated to grow the business in order to make it more profitable, which facilitates upward mobility, higher wages, better benefits, potential equity positions, and, perhaps most importantly, a sense of camaraderie and purpose.

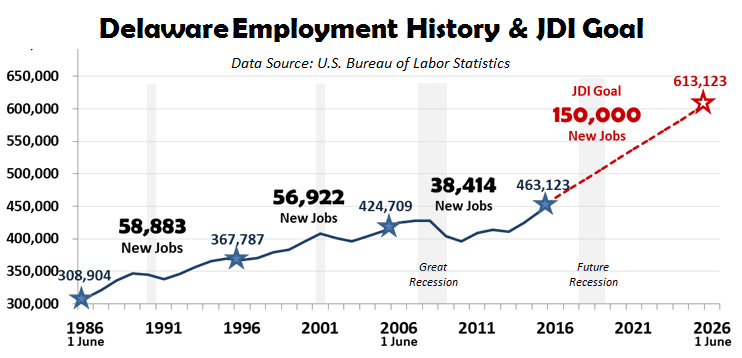

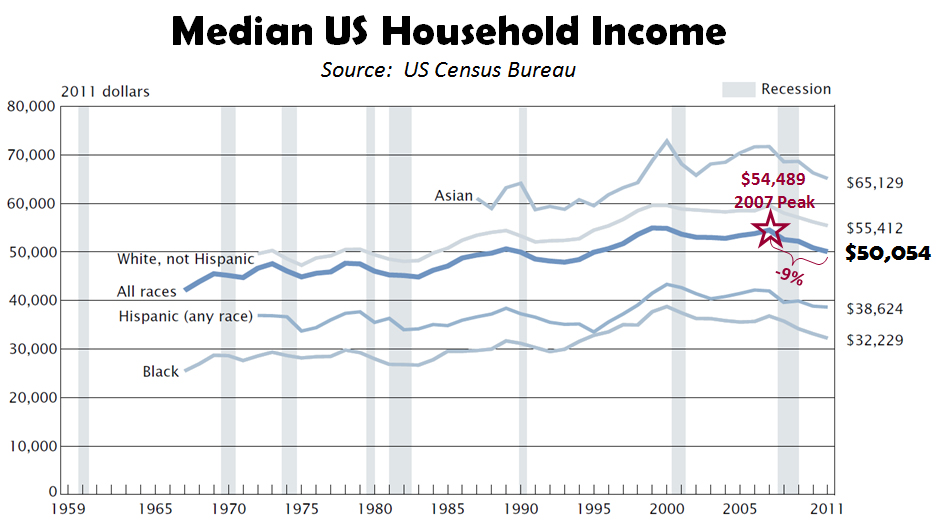

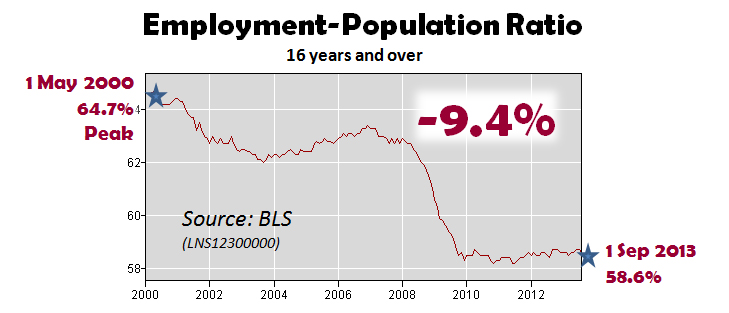

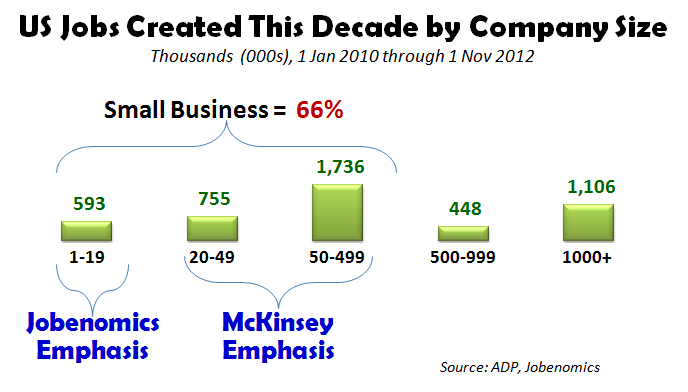

Job creation is the number one issue facing U.S. in regard to economic growth, sustainment and prosperity. Jobs do not create jobs, businesses do, especially small businesses that currently employ 80% of all Americans and created 80% of all new jobs since the end of the Great Recession.

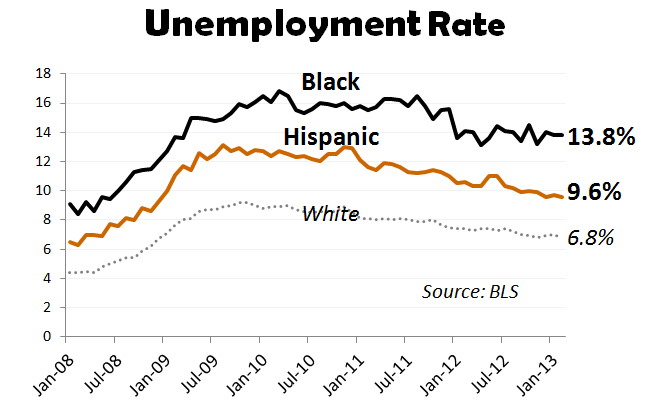

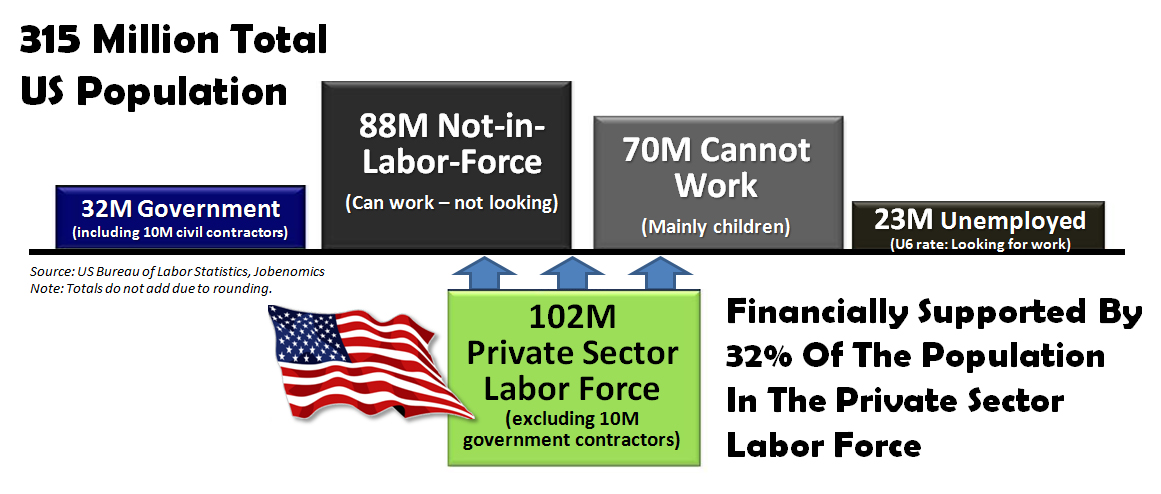

Unfortunately, America is focused on big business and government employment solutions that have not been very effective growing the U.S. labor force. In fact, the U.S. labor force is in a state of decline as evidenced by the eroding middle-class and the transformation from standard full-time to part-time and contingency workers. With the next fifteen years, Jobenomics forecasts that the contingent workforce will replace traditional full-time workforce as the dominant force of labor in the United States—a trend that is largely unknown to policy-makers and the American public.

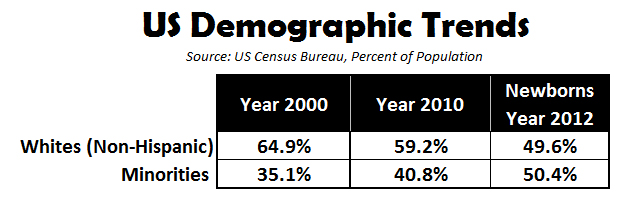

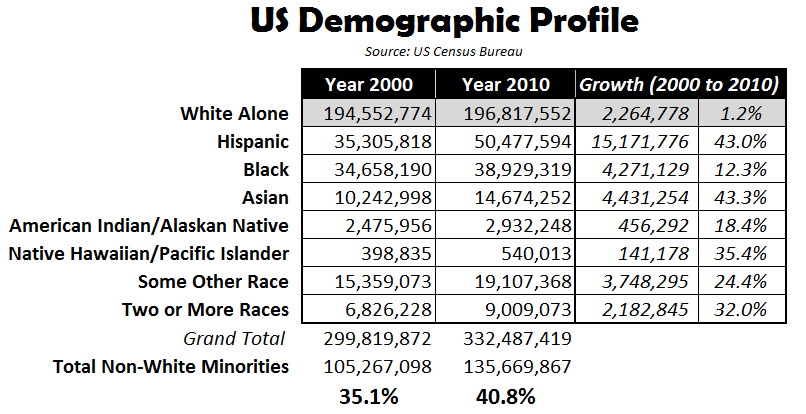

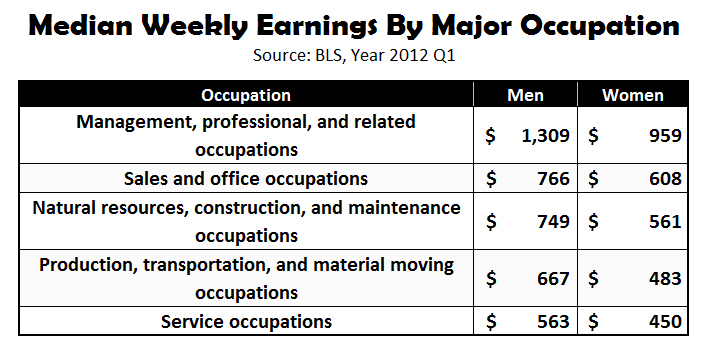

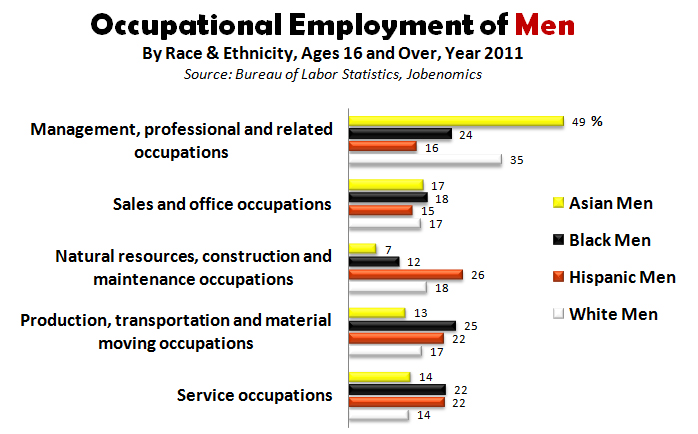

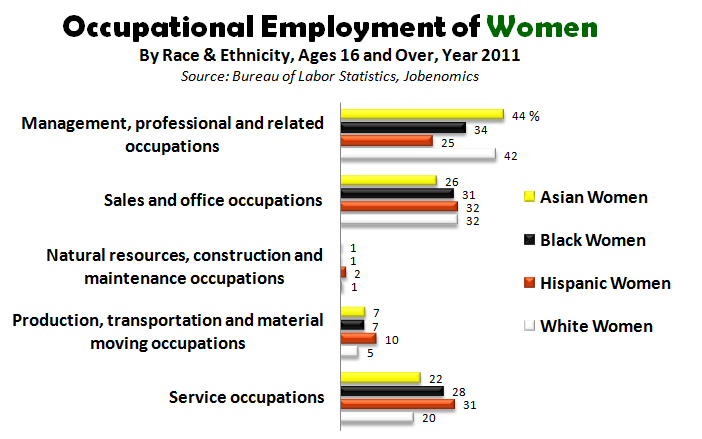

Jobenomics asserts that the four demographics with the highest need and growth potential include women, minorities, new workforce entrants, and the large cadre of financially distressed citizens who want to work or start a business. These demographics are ideally suited for the accommodating the growing contingent workforce and attracting new labor force entrants that often do not share the same employment dream of older generations.

Jobenomics believes that new small, emerging and self-employed businesses could create 20 million new jobs within a decade, if properly incentivized and supported. Notwithstanding filling the 5+ million open U.S. jobs positions, the emerging Energy Technology Revolution (ETR) and the Network Technology Revolution (NTR) could create 20 million net new American jobs within a decade given proper leadership and support.

Using the Jobenomics Community-Based Business Generator process of mass-producing highly repeatable and scalable “turn-key” small and self-employed businesses, America writ large could create tens of millions of jobs that would transform the U.S. labor force, middle-class and economy as well as providing hope and jobs for marginalized urban and rural American communities.