Jobenomics July 2017 Employment Report Analysis

Executive Summary. The two primary sources for U.S. labor force data are the monthly U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Employment Situation Summary, a monthly summary of all U.S. government and private sector employment, and the ADP National Employment Report, a monthly survey of employment by 400,000 U.S. private sector businesses by the ADP Research Institute in collaboration with Moody’s Analytics.

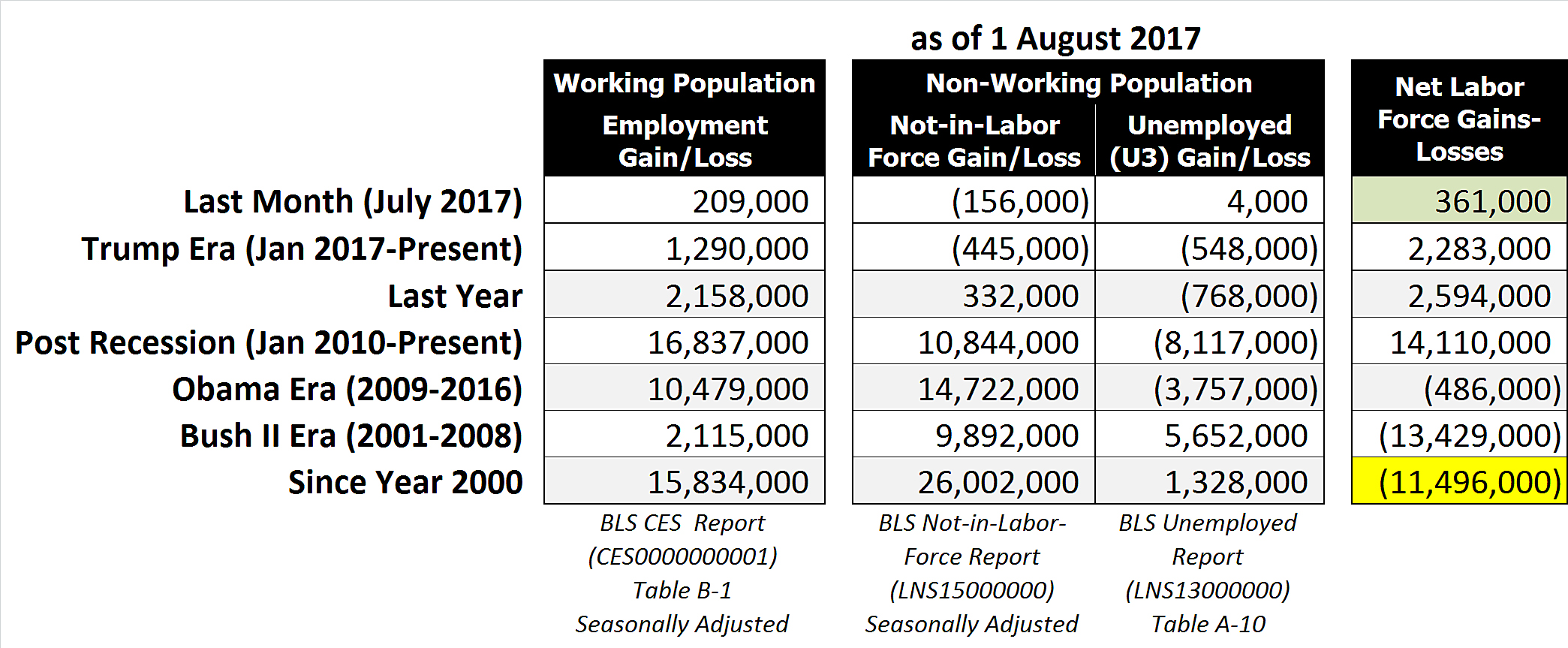

Jobenomics Analysis of the BLS Employment Situation Summary Report. To get a strategic perspective of the state of the U.S. labor force and workforce issues facing the United States, one must compare the private sector Working Population (Employed) against the Non-Working Population (U3 Unemployed and Not-in-Labor-Force).

Working Versus Non-Working Populations

As shown, from 1 January 2000 to 1 August 2017, the private sector’s Working (Employed) population rose by 12% compared to a rise of 38% in the Non-Working Population. Jobenomics defines the Non-Working Population as Not-in-Labor Force (that rose by 39%) and the Officially U3 Unemployed (which is still 35% higher today than in year 2000 in terms of numbers of unemployed). While the overall trend since the turn of the Century is a negative one, recent employment gains are positive.

U.S. Labor Force Gains and Losses Since 2000

In regard to the Working Population, the 4 August 2017 BLS Employment Situation Summary reports that the United States produced a total of 209,000 new jobs in July—a solid job gain but a number below the 250,000 new job standard advocated by most economists in order to grow the U.S. economy a robust rate to compensate for future financial downturns. In regard to the Non-Working Population, the BLS reports 156,000 less people are now enrolled in the Not-in-Labor-Force category (a BLS category of for people who can work but choose not to work). This 156,000 person reduction in Not-in-Labor-Force category is a positive indicator that able-bodied citizens that were sidelined from working (due to frustration, welfare, early retirement, education, etc.) are beginning to return. The BLS also reports that the Official U3 Unemployment rate dropped slightly from 4.4% to 4.3% (a post-Great Recession low) even though the number of unemployed people actually grew by 4,000 people from 6,977,000 in June to 6,981,000 in July. Note: unemployment rates are calculated as a percentage of the civilian labor force that grew from 160,145,000 in June to 160,494,000 in July, a gain of 349,000—a movement in the right direction. As calculated by Jobenomics, the overall U.S. labor force situation grew by a net 361,000 (highlighted in green above), which is a healthy number as well as a positive barometer for economic growth.

From a Trump Era perspective, during the 7-months (January through July 2017) of the Trump presidency, employment gains amounted to 1,290,000 workers, for an average of 184,286 per month, which is below the desired threshold of 250,000 jobs per month. However, the Not-in-Labor-Force (i.e., capable of working but not looking) and U3 Unemployment (i.e., no job but looking for work) categories sustained significant reductions, 445,000 and 548,000 respectively. Collectively, the labor force net gain is 2,283,000 in the first 7-months of the Trump Administration, which compares very favorably with the Obama Administration’s 8-year labor force net loss of 486,000 workers and the GW Bush Administration’s 8-year net loss of 13,429,000 workers.

Since the end of the Great Recession, from 1 January 2010 to 1 July 2017, the U.S. labor force net gain was 14,110,000 workers, of whom 16,837,000 entered the labor force, 10,844,000 voluntarily departed, and 8,117,000 fewer people were officially unemployed.

During the 8-years/96-months of the Obama Era (1 January 2009 through 31 December 2016), the U.S. labor force lost a net 486,000 jobs, of whom 10,479,000 entered the labor force, 14,722,000 voluntarily departed, and 3,757,000 fewer people were recorded as officially unemployed. It is important to remember that President Obama took office during the last 6-months of Great Recession.

During the 8-years/96-months of the GW Bush Era (1 January 2001 through 31 December 2008), the U.S. labor force lost a net 13,429,000 jobs, which included the first 12-months of Great Recession, the 8-months of the 2001 Recession (March 2001–November 2001), as well as the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks. Of the net loss 13,429,000 jobs, 2,115,000 entered the labor force, 9,892,000 voluntarily departed, and 5,652,000 more people were recorded as officially unemployed.

From the beginning of 21st Century (1 January 2000 to 1 July 2017), the American labor force is weaker by a net 11,496,000 workers (highlighted in yellow). This weakness is exacerbated by population growth of 43 million additional American citizens today compared to 2000 (282 million versus 325 million) as well as the rapid rise of contingent part-time workers in comparison to traditional full-time workers.

As of 1 July 2017, the BLS reports that the private sector workforce consists of 124,257,000 workers or only 38% of the total population of 325 million. Of the private sector workforce, approximately 60% are traditional full-time workers and 40% are contingent workers (part-timers, freelancers, independent contractors, etc.) who generally-speaking earn far less income than traditional workers and often receive little or no benefits. The U.S. economy cannot be sustained without strengthening of the U.S. private sector’s labor force.

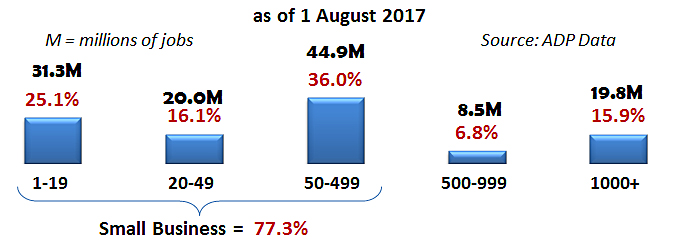

Jobenomics Analysis of the ADP National Employment Report. The July 2017 ADP National Employment Report, released on 2 August 2017, reported 178,000 U.S. non-farm private sector new jobs, which is 27,000 less than reported by the BLS. Note: the 209,000 new jobs reported by the BLS include 205,000 new non-farm private sector jobs and 4,000 new government workers. ADP does not report on unemployment or workforce departures. However, the ADP report provides much greater visibility on labor force contributions made by small, medium and large-scale businesses.

Of the 178,000 U.S. non-farm private sector new jobs, the ADP National Employment Report calculates that small businesses (1-49 employees) produced 50,000 new jobs (28.1% of the total), midsized businesses (50-499 employees) produced 83,000 new jobs (46.6%), and large businesses (500 or more employees) produced 45,000 new jobs (25.3%). For the purposes of this report, Jobenomics classifies small business as having 1-499 employees (the definition supported by the U.S. Small Business Administration), midsized business as 500-999 and large businesses as 1000+ employees. In addition, Jobenomics considers micro-businesses having 1-19 employees, which includes self-employed businesses.

U.S. Private Sector Employment by Company Size

As reported by the ADP National Employment Report, small businesses are undeniably the dominant employer and job creator in the United States. According to ADP, small businesses with less than 500 employees employ 77.3% of all private sector Americans with a total of 96,201,000 employees—over 3.4-times the amount of large businesses with more than 500 employees that have 28,328,000 employees. Micro and self-employed businesses with 1-19 employees employ 1.6-times the number of major corporations with over 1,000 employees (31,267,000 versus 19,819,000).

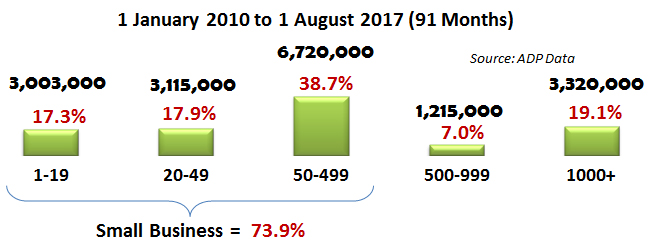

U.S. Private Sector Jobs Created This Decade by Company Size

Since the beginning of this decade, small businesses created 73.9% of all new jobs in the United States. Small businesses with less than 500 employees created 2.8-times more jobs as large businesses with over 500 employees, or 12,838,000 versus 4,535,000 new jobs respectively. Micro and self-employed businesses with 1-19 employees created 0.9-times (90%) the number of major corporations with over 1,000 employees (3,003,000 versus 3,320,000).

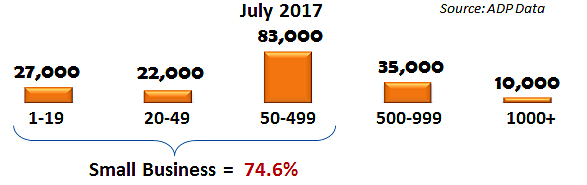

U.S. Private Sector Jobs Created Last Month by Company Size

Last month (July 2017), U.S. small business created 74.6% of all new jobs, which compares favorably to 68.4% in June, 77.2% in May, 72.2% in April and 81.9% in March. Micro-businesses (1-19 employees) created 27,000 jobs (15.1% of the total) compared to only 10,000 (5.6%) of major corporations. While most of the America’s and the world’s attention is focused on the Trump Administration’s big business focus (e.g., reshoring jobs and trade policies), it is small business that produced 132,000 out of the 178,000 new private sector jobs last month, whereas, despite all the political rhetoric and media attention, big business (500+ employees) created only 45,000 new jobs.

Data Analysis and Discussion.

Most economists believe that economic growth depends on employment and GDP growth. The ideal rate for U.S. GDP growth is around 3%. Any GDP growth below 2% is considered sclerotic growth that makes the U.S. economy vulnerable to financial downturns.

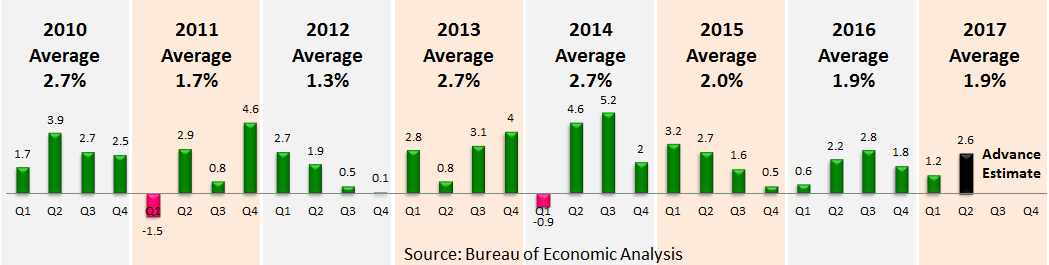

Real GDP Quarterly Percent Change This Decade

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), during the post-recession recovery period from Q1 2010 through Q1 2017, U.S. GDP averaged 2.25%. In 2015 and 2016, U.S. GDP grew by subpar rates of 2.0% and 1.9% respectively. During the first two quarters of the Trump Administration, GDP averaged 1.9%.

Q1 2017’s GDP “revised” estimate (latest) was a subpar 1.2%—up from an abysmal “advance” estimate of 0.7%, equal to the 1.2% “second” estimate, and down from the 1.4% “third” estimate. Regardless of estimate, Q1 GDP data was not good news for the new Trump Administration. However, these low percentages can be rationalized as a carryover from the previous Administration.

Q2 2017’s GDP “advance” estimate (latest) is 2.6%—a significant improvement over Q1 and a good sign for President Trump’s stated goal of raising U.S. GDP growth to 4.0%. In regard to other Q2 2017 prognosticators, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow forecast model for Q2 2017 is 2.8%, down from a 4.3% forecast on 1 May 2017. It is interesting to note that the Fed’s GDPNow forecast model for Q1 2017 started at a high of 3.1% on 2 February 2017 and decreased steadily to 0.2% by the end of the reporting period. Hopefully, this downward trend will not be repeated for Q2 2017. The “Blue Chip” survey of the bottom 10 and top 10 leading business economists forecast that Q2 2017 growth will eventually fall between 2.3% and 3.2%.

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), during the post-recession recovery period from Q1 2010 through Q2 2017, U.S. GDP averaged 2.1%. In 2015 and 2016, U.S. GDP grew by subpar rates of 1.9% and 2.0%. Q1 2017’s GDP projection (third estimate) was an abysmal 1.4% (up from the 0.7% initial estimate and the 1.2% second estimate. It appears that the final BEA Q1 2017 GDP will be significantly below President Trump’s bold plan “to return to 4% annual economic growth.” Hopefully, Q2 2017’s GDP growth rate will be much more robust.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow forecasting model for Q2 2017 was initially 4.3% on 1 May 2017 but subsequently downgraded to 2.7% as of 6 July 2017. It is important to note the Fed’s GDPNow forecasting model for the Q1 2017 initial forecast was 3.1% on 2 February 2017 and continually decreased to 0.2% by the end of the reporting period. As annotated by the Atlanta Fed, the “Blue Chip Economic Indicators” survey of a range of Top 10 and Bottom 10 forecasts by leading business economists project Q2 2017 growth at 2.8%.

As of 4 August 2017, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta released its preliminary GDPNow forecast for Q3 2017 is 3.7%. As annotated by the Atlanta Fed, the “Blue Chip Economic Indicators” survey of a range of Top 10 and Bottom 10 forecasts by leading business economists project Q3 2017 growth at a high of 3.0% and a low of 1.8%.

While GDP growth does not insure employment growth, sclerotic GDP growth discourages business hiring, consumer spending and labor force expansion. Sclerotic GDP growth also discourages lower rates of unemployment and voluntary workforce departures. Negative GDP growth creates recessions and depressions depending on the severity and longevity of the contracting economy.

The period of sclerotic GDP growth from 2000, has dramatically impacted the American middle-class and the U.S. labor force that this is weaker by 11.5 million workers today than at the beginning of the 21st Century. For most American workers, real wages (purchasing power) have not increased for decades and are not projected to improve anytime soon. America’s aggregate household income has shifted from middle-income to upper-income households, causing many middle-class workers to leave the workforce altogether. The solution to building a robust middle-class is to accelerate GDP growth, which requires the creation of more productive private sector jobs, which, in turn, can only be generated by a massive expansion of the small business sector.

Concluding Thoughts. President Trump’s vision of a “dynamic and booming economy” is one that can produce a GDP growth rate of “4% over the next decade”. This vision ultimately depends on mass-producing business, especially small business, in sufficient quantities to create 25 million net new jobs. Sclerotic (0% to 2%) or recessive (negative) GDP rates depreciate a government’s legitimacy. Robust GDP growth of over 3% will have the opposite effect. If the Trump Administration can achieve 4% in a stable global economy, Americans will be euphoric in a booming economy. This feat will not be easy. The last year the United States reached 4% in a single year was 2001. The last time that the United State reached 4% in ten consecutive years during the last 50-years was never (3.5% was the highest from 1976 to 1985). Notwithstanding, if the Trump Administration can tie the 3.5% record over the next decade, they will be vindicated and worthy of much praise.

According to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office’s 2017 to 2027 Budget and Economic Outlook report, “over the next five years, the monthly increase in nonfarm payroll employment, which is estimated to average 160,000 jobs in the first half of 2017, is projected to settle down to an average of 64,000 jobs.” If the CBO outlook is correct, the next decade is likely to produce only 9 million jobs, which is far short of President Trump’s projection of 25 million new jobs. Note: last year’s BLS Employment Projections: 2014-24 Summary report forecasts that the United States will produce only 9.9 million new jobs over the next decade.

Jobenomics tends to agree with the CBO and BLS for the reasons discussed in the Jobenomics 20-part series entitled President Trump’s New Economy Challenge. However, the Trump Plan can be amended to change CBO and BLS labor force projections from negative to positive. With proper leadership, the Administration can lift tens of millions of Americans out of poverty by making the following four structural changes to President Trump’s economic and job creation plan:

- Balancing the traditional standard industrial economy with the newly emerging nonstandard digital economy,

- Mitigating the mass-exodus of able-bodied workers who are voluntarily departing the U.S. labor force for lives of dependency and alternative (often illicit) lifestyles,

- Addressing the challenge of the ever-growing contingency workforce that will soon be the dominate form of labor in the United States, and

- Mass-producing small and self-employed businesses—the engine of the U.S. economy—and the employer of the vast majority of Americans.

If the Trump Administration can achieve a sustainable 4% GDP in a stable global economy, Americans and the world will be euphoric. This feat will not be easy. If the Trump Administration can exceed 4% GDP growth even for a few years, his Administration will be worthy of much praise.

About Jobenomics: Jobenomics deals with economics of business and job creation. The non-partisan Jobenomics National Grassroots Movement’s goal is to facilitate an environment that will create 20 million net new middle-class U.S. jobs within a decade. The Movement has a following of an estimated 20 million people. The Jobenomics website contains numerous books and material on how to mass-produce small business and jobs as well as valuable material on economic and business trends.

Recommended reading

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Non Aams

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Casino Non Aams

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Sports Betting Sites

- Online Casinos UK

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Non Gamstop UK Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Top Casino Sites UK

- Best Casino Sites UK

- UK Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Best Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Crypto Casinos

- Jeux Casino En Ligne

- Meilleur Site Casino En Ligne Belgique

- I Migliori Casino Non Aams

- ライブカジノ ポーカー

- 本人 確認 不要 オンライン カジノ

- 코인카지노

- букмекерские конторы

- カジノ バカラ

- ライブカジノ バカラ

- Casino Avec Bonus Sans Depot

- Jouer Au Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Francais

- Casinos En Ligne