Our Recent US Employment Trends article indentified the three most important US employment sectors: private sector service-providing industries, private sector goods-producing industries, and the government sector. This article examines private sector goods-producing industries with emphasis on manufacturing and construction industries.

As discussed in our 30-Year US Employment Trends article, US private sector goods-producing industries have deteriorated by 25% over the last three decades. If adjusted for US population growth deterioration of this sector exceeds 50%. In lieu of a significantly improved US economy, Jobenomics forecasts that goods-producing industries decline may stabilize but will produce few, if any, new private sector jobs in the near future.

Private sector goods-producing industries include: Manufacturing (11.8 million jobs), Construction (5.5 million), Nondurable goods (4.4 million), and Mining/Logging (700,000 jobs). Manufacturing and construction are the two largest and most influential categories.

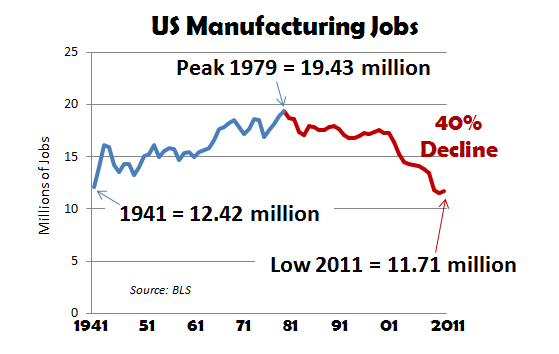

Manufacturing. US manufacturing hit its peak in 1979 with 19.43 million jobs. Today, US manufacturing only employs 11.71 million people, a 40% decline from its peak in 1979 and the lowest since 1941. As a percent of population, manufacturing has suffered a 55% decline (the US population in 2011 is 312M, compared to 225M in 1979). As shown by the very small uptick on the chart, manufacturing has increased 1.6% over the last year for at total 189,000 jobs. While this good news, the big question is will this micro-trend continue?

From a Jobenomics perspective, manufacturing is not, and, will not be a significant contributor to US employment in the next five years. 189,000 yearly jobs equates to a monthly average of 16,000 jobs. Measured against the traditional benchmark of 250,000 monthly jobs needed for economic recovery, 16,000 jobs equates to a meager 6% contribution. Looking back to the start of the Great Recession (January 2008), manufacturing is down by almost 2 million jobs, so this recent uptick is relatively insignificant.

From a more strategic perspective, major corporations are the driving-force for manufacturing employment. These corporations are disinclined towards hiring domestic workers and will likely remain so disposed in the near future. The chief reason is US economic uncertainty. As long as US GDP muddles along at near stall speed with storm clouds on the horizon, corporations will continue to be reluctant to retool or build new plants. Instead, cash-rich corporations will continue to invest their trillions of dollars worth of cash reserves in overseas emerging markets (China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and other countries that have robust GDP growth) and in the financial markets. US government over-regulation, high US labor rates and unions, makes foreign manufacturing much more appealing than domestic pursuits. While there is a lot of political rhetoric about reducing regulation and promoting exports, it is likely that nothing meaningful will happen anytime soon. Devaluation of the US dollar has been helpful making US exports more competitive overseas, but devaluation adds to corporate uncertainty as well as poor consumer and investor confidence. Unemployment and aging population are also factors. 78 million baby-boomers are likely to spend more on services than big-ticket manufactured items.

Construction. The US construction industry employs 5.5 million Americas in three sectors: residential (2M jobs or 37% of the total construction industry), nonresidential (2.7M or 48% of total), and heavy & civil engineering (843,000 or 15% of total). Nonresidential deals mainly with commercial properties. Heavy & Civil Engineering deals mainly with infrastructure projects, like highways, bridges, and dams.

Since the employment peak in the mid to late 2000s, the overall commercial industry declined 40%. During the same time period, residential construction declined a whopping 71%, nonresidential declined 30%, and heavy & civil engineering declined 20%. Over the last year, the overall construction industry has stabilized with only minor losses of jobs. From a Jobenomics perspective, this recent period of stabilization is temporary with more jobs losses in the near future, unless the US economy significantly rebounds, investor confidence markedly improves, and financial institutions make credit more accessible to builders. None of these three conditions appear likely in 2012.

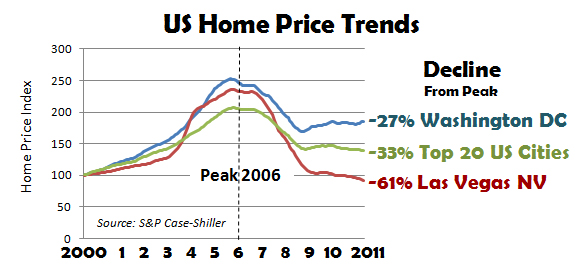

Residential is currently the driving-force in the construction industry. The Great Recession was caused mainly by the housing bubble burst. In the wake of the Great Recession, housing prices collapsed. As shown above, homes in the top 20 US cities lost 33% of their value. Some metropolitan areas, like Washington DC, fared slightly better (-27%) largely due to the federal government. On the other end of the scale, Las Vegas was hammered with -61% losses. While home values seemed to stabilize briefly in 2009-2010, the top 20 city composite index lost 3.4% in 2011.

The 2012 residential housing market forecast is cloudy. Foreclosures, underwater mortgages, delinquencies, and strategic defaults (walking away from home mortgages) are still major challenges. Conversely, home affordability is now more in par with renting. Buyers who have stayed on the sidelines may return to the market. However, buyers are aware of the fact the home prices could continue to fall. A new wave of foreclosures is predicted as banks begin to release their plentiful inventory of reprocessed homes. According to some economists, home prices could fall as much as 25%, which, in turn, would keep the residential construction industry depressed.

The commercial and heavy construction industries are poised for a period of growth. However, McGraw-Hill Construction, a mainstay in construction industry forecasting, predicts that 2012 construction starts will remain flat. Significant upsides in private sector construction financing (plants, warehouses, hotels, and commercial buildings) will be offset by large declines in public sector construction projects funded by municipal, state and federal governments. New public sector projects like school, healthcare, electric utility and other public works programs (bridges, parks, roads) are problematic due to fiscal constraints at all levels of government. In addition, new industry entrants face challenges with access to capital. Strict lending standards exclude many general contractors from being eligible for loans.